Research & Insights

Our Research Process

Throughout our history, Bridgewater has focused on building the best possible understanding of global economies and markets. These unique insights drive our innovative investment engine, deliver returns for our clients, and inform global economic policy.

On a mission to uncover timeless and universal investment principles, our unique meritocratic culture and cutting-edge technology allow us to systematize and compound our insights over time so that our collective understanding is greater than that of any individual.

As a global macro-investment manager, we take a diversified approach spanning more than 150 different markets. With deep expertise in portfolio construction and risk management, we develop insights and design strategies to deliver value to our clients through any economic environment.

Selected Insights from Our Research Library

April 3, 2025

Head of the Portfolio Strategist group Atul Lele joins the Fiduciary Investors Symposium in Singapore to discuss the paradigm shift from globalization to modern mercantilism, and how investors can construct resilient portfolios in today’s increasingly complex macroeconomic and geopolitical environments.

March 19, 2025

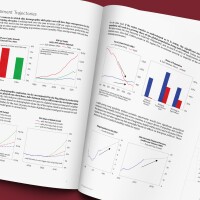

Policy has shifted to prioritize energy security and industrial competitiveness over climate leadership. This will steer investment to the most economical energy sources, driving continued growth in renewables and fossil fuels—but slower decarbonization.

March 10, 2025

For decades, America has consumed much more than it produces, financing persistent trade deficits with debt that foreign investors are happy to buy. President Trump is unwilling to accept this state of affairs. In a guest essay for the New York Times, co-CIO Karen Karniol-Tambour describes what this shift means for Europe’s economic and security paradigm, the changes that are needed, and the barriers to reform.

March 4, 2025

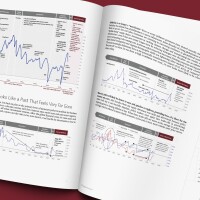

Daily Observations editor Jim Haskel sits down with head of contra-currencies Hudson Attar and portfolio strategist Alex Smith to discuss the recent gold rally and the type of diversification gold can provide.

February 6, 2025

Energy expert Daniel Yergin sits down with Bridgewater senior portfolio strategist Atul Lele to discuss supply and demand dynamics across energy markets and their implications for investors.

January 30, 2025

Co-CIO Bob Prince discusses the gradual drift of economic conditions toward equilibrium and whether this process has room to run.

January 6, 2025

With central banks on the verge of achieving their goals—supporting stability, profits, and asset prices—global political shifts risk upsetting the balance. Our CIOs describe these dynamics and what they mean for investors.

November 21, 2024

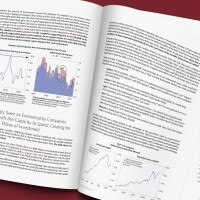

Following Trump’s victory, we assess the supply and demand picture for US debt, and what it means for yields going forward. To do so, it is important to look at the total debt in the economy—not just government debt.

November 12, 2024

At the recent Yahoo Finance Invest conference, Co-CIO Karen Karniol-Tambour shared her thoughts on what’s next for growth and inflation, Fed policy, the impact of Trump’s policy agenda, and how we’re processing the flow-through to markets. See Important Disclosures and Other Information.

October 16, 2024

Where is AI today, and where is it going in the near future? In this video presentation, Bridgewater’s AIA Labs Chief Scientist Jas Sekhon provides a framework that can help answer those questions and resolve a key paradox that currently exists in the AI landscape.

October 3, 2024

Head of Client Service and BDO Editor Jim Haskel speaks with Bridgewater founder and CIO mentor Ray Dalio aboard his OceanXplorer ship in Singapore about the five big forces that shape history and markets and how they’re playing out today.

September 25, 2024

In a moderated conversation, Rohit and Bob discuss how they each approach portfolio resilience at their respective organizations and the potential opportunities they see in markets today.

September 17, 2024

Some of the largest drivers of US equity outperformance cannot be counted upon going forward. A lot depends on the ability of US tech to deliver and AI to unleash productivity across sectors.

September 2024

As part of the 30th anniversary of the relationship between Bridgewater and GIC, the entity that is responsible for managing Singapore’s international reserves, our two organizations have led a series of joint research projects to identify and assess the issues we think are most important for investors to grapple with in the years ahead. In this videocast, Head of Client Service and Editor of the BDO Jim Haskel discusses the takeaways of that work with Jeffrey Jaensubhakij, Group Chief Investment Officer of GIC; Liew Tzu Mi, Chief Investment Officer for Fixed Income & Multi Asset and Chair of the Sustainability Committee; and our own co-Chief Investment Officer Greg Jensen.

September 10, 2024

Co-CIO Greg Jensen explains that the greatest bubbles require a transformational technology and a ripe macro and monetary backdrop. We now have both—so he believes the AI bubble is ahead of us, not behind us.

August 14, 2024

Ajay Banga, President of the World Bank, sits down with Bridgewater CEO Nir Bar Dea to discuss Africa’s economic trajectory and how it creates challenges and opportunities for global investors.

August 2024

The demographic boom in the working-age population in sub-Saharan Africa is one of the long-term forces that can shape the world in the coming decades. In this research, we explore this dynamic in depth, its implications for the region’s role in the global economy, and how decisions made by policy makers, investors, and the private sector can forge alternative paths.

August 23, 2024

The CIO of Australia’s sovereign wealth fund, managing $300 billion AUD, joins us for a conversation on their total portfolio approach and some of the most challenging questions facing investors.

July 7, 2024

Co-CIO Karen Karniol-Tambour recently joins Alex Shahidi on the latest episode of his podcast, The Insightful Investor, to share insights into her professional journey, Bridgewater's current market outlook, and how to think about building great portfolios in this environment.

June 24, 2024

Co-CIO Karen Karniol-Tambour describes how we’re in the midst of a transition from an exceptionally low cost of capital to more moderate levels. But bond yields still need to rise to set a price of capital that is sustainable for the world we’re in, compensating for structurally higher fiscal stimulation and inherently inflationary spending on things like AI investments, remilitarization, rebuilding supply chains to reduce reliance on China, the energy transition, and energy security.

June 18, 2024

Throughout history, certain companies have dominated the equity market, but co-CIO Bob Prince explores how the process of creative destruction makes staying on top for long periods of time very difficult.

May 20, 2024

While AI investment isn’t yet a major driver of economic growth, co-CIO Greg Jensen says it looks poised to rise rapidly from here—with the potential to shape the business cycle well before AI is in widespread productive use.

May 7, 2024

At the Milken Institute’s 2024 Global Conference, co-CIO Karen Karniol-Tambour shares her thoughts on the macro outlook, touching on where to find geographic diversification, how we’re approaching geopolitical risk, the impact of AI on inflation, and more.

April 25, 2024

As most major economies are seeing their working age populations stagnate or shrink, sub-Saharan Africa’s is growing rapidly and projected to be larger than China’s in about a decade. If the region can also increase its productivity growth, it will begin to emerge out of poverty and gradually become relevant to global investors.

April 18, 2024

Bridgewater co-CIO Karen Karniol-Tambour joined a panel conversation at Semafor’s first World Economy Summit to discuss the evolving macroeconomic environment, fiscal policy, the bond market, demand for U.S. assets, and the strength of the U.S. dollar.

April 1, 2024

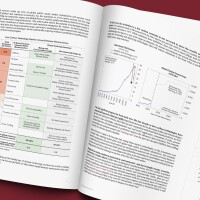

Head of Sustainability Research Daniel Hochman and Senior Researcher Jeremy Ng explore how achieving the world’s ambitious climate goals will require rapidly scaling economically viable technologies, while also innovating, incentivizing, and investing in less mature technologies that are not yet cost-competitive.

February 23, 2024

Maximizing the benefits of geographic diversification can be highly beneficial for portfolios. But doing so can be difficult because many economies are closely linked to US conditions, making their markets highly correlated to US assets investors already own. Co-CIO Karen Karniol-Tambour explores some of the markets she sees as the most diversifying.

February 22, 2024

Bridgewater alum, author, and investor Paul Podolsky shares how he’s assessing Russia and its threat to the global order following the death of Alexei Navalny, what it takes for economies to succeed in the modern world, and the implications for investors.

January 3, 2024

The secular investment landscape looks more like decades past than the last 20 years, while dynamics like AI and climate change will likely shape the world in unprecedented ways. Co-CIO Karen Karniol-Tambour describes this new era of investing.

November 30, 2023

What happens when cognitive tasks can be done at zero marginal costs? Co-CIO Greg Jensen explores some of the potential impacts that advancements of AI/ML technology could have on companies and the economy, including an extreme scenario that could potentially produce “explosive growth.”

October 2, 2023

The impacts of AI on the economy will depend both on how the technology evolves and how quickly and effectively it is implemented. Co-CIO Karen Karniol-Tambour shares how we are interpreting the growing literature on the topic and tracking the process in real time.

September 20, 2023

Bridgewater co-CIO Karen Karniol-Tambour joins “Bloomberg Wealth with David Rubenstein” for a wide-ranging discussion on Bridgewater’s current leadership and culture, her career journey, and our outlook on markets and economies.

November 30, 2022

The publicly traded firms in a handful of emissions-intensive sectors are responsible for about 60% of all global emissions. By allocating capital to climate solutions and carbon improvers in these sectors, investors can make progress toward their net zero goals, even if that leads to higher spot portfolio emissions than if they were to cut these emissions-intensive sectors altogether.

Featured Research

We are constantly monitoring present day events and drawing lessons from history to shape and refine our understanding for how markets and economies work. Explore a collection of our research on topics ranging from debt crises to sustainable investing.