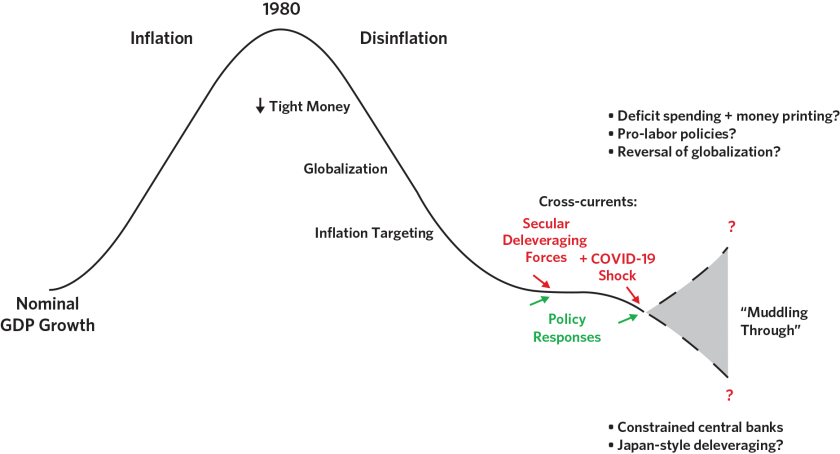

We have been describing for some time a likely paradigm shift in economies and markets, as the forces that drove the environment over the last decade were at their limits. We expected a new paradigm to come about as a result of weak growth and secular disinflationary forces in an environment of large promises (via debt and government programs) and growing domestic and internal conflict at a point when central bank policy was near its limits. The result of this environment was uncertain, but we thought it likely that policy makers would need to shift to an era of fiscal and monetary coordination more like the economies of the 1930s-1940s. This would eventually lead to a testing of how far fiscal policy funded by central banks could push economies. Unfortunately, the impact of the coronavirus took us by surprise (and we weren’t positioned for many of the recent market moves), but that shock has in effect pulled forward a paradigm shift that we expected would unfold much more gradually over time.

We expect that these new policies (fiscal and monetary) will last beyond the virus and how these policies are used will drive markets and economies going forward in a way that is different from past cycles. Interest rates are now near zero, and policy makers across the developed world are confronting the reality that monetary policy alone is impotent in the face of this downturn and that a coordinated monetary and fiscal response (what we have called “Monetary Policy 3/MP3”) will be needed. The Fed announcing unlimited QE at the same time as the largest fiscal push in history is a remarkable step in this direction. In the shorter term, there is a wide range of outcomes associated with the progression of the virus itself and whether fiscal responses around the world will be sufficient to fill the massive hit to incomes. Longer term, policy makers will likely test the limits to which deficit monetization can be pushed, which carries its own set of risks and the likelihood of highly divergent outcomes across economies (e.g., reserve currencies like the dollar having more ability to print and monetize before being confronted with currency and/or inflation problems). To us, this environment and the range of potential outcomes call for reducing risk and bolstering diversification in all forms.

The key forces we have described that are driving the need for a new paradigm are: 1) weak growth and secular disinflationary forces in the developed world; 2) too many IOUs in the form of debt and other obligations relative to the incomes that will exist to pay for them; 3) growing conflict both within and between countries; and 4) central banks nearly out of monetary fuel. The pandemic has exacerbated each of these factors and, as a result, has significantly accelerated the paradigm shift.

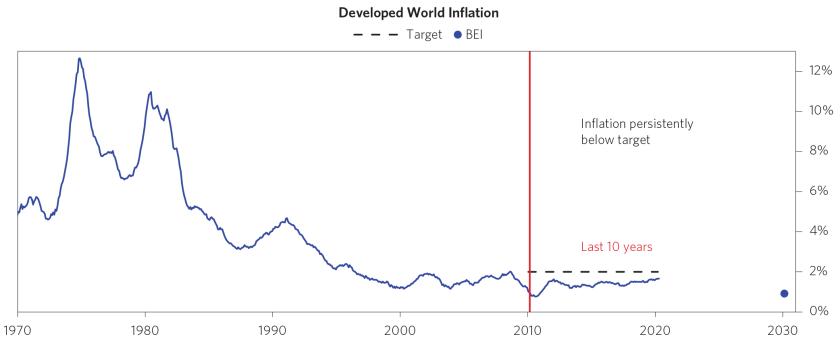

- Weak growth and secular disinflationary forces: The deflationary income shock from the virus is producing what may be the fastest-moving contraction in economic activity in history, exacerbating already weak growth and secularly low inflation. The magnitude of the downturn will be huge: most economies look to be tracking toward a 10-15% hit to GDP in the short term, and if this isn’t sufficiently offset by policy, there will be an even bigger self-reinforcing contraction and a risk of outright deflation.

- Too many IOUs: Pre-coronavirus, we estimated total IOUs would reach roughly 11x GDP in the US by 2030, with a similar picture across developed economies. The coronavirus disruption has opened up a massive gap in incomes, the fall in equity prices has hurt many savers’ ability to fund their liabilities, and governments will have to take on further debts and obligations to deal with the disruption and its aftermath. These factors make the IOU situation significantly worse, demanding a new policy response to deal with it.

- Growing internal and external conflict: Wealth and income gaps were already contributing to populism and rising political conflict despite an expanding economy and falling unemployment. The downturn will hit those worst off the hardest, and while the speed and size of the policy response we have seen in the US so far is promising, more will be needed globally, and differences in views on how to divide the shrinking pie have the potential to make political conflict more acute. And while we don’t want to exaggerate the risks, it’s worth noting that historically crises like this can be catalysts for revolutions and wars (and we’ve already begun to see finger-pointing between countries).

- Central banks out of monetary fuel: Central banks entered this crisis with limited ability to ease through traditional monetary tools. Over the past few weeks, interest rates have been brought to near zero, bond yields have fallen below 1% in most of the developed world, and central banks have launched the largest global money printing program in history.

We have described the two main elements of the new policy paradigm required to deal with these challenges: fiscal policy will need to become much more proactive and central banks will likely lag inflation and push as hard as they can to stimulate economies. This new policy paradigm is now taking shape.

- Fiscal policy will need to become much more proactive: The very nature of this crisis is that it cannot be solved by monetary policy alone, as central banks can’t effectively direct money where it is needed to fill the gap in incomes. There is now an immediate need to shift to what we’ve been discussing for a long time—Monetary Policy 3—which is essentially coordinated monetary and fiscal policy, with central banks monetizing fiscal deficits. The Fed announcing unlimited QE at the same time as $2 trillion in stimulus spending is in effect a massive deficit monetization, and we expect to see more around the world.

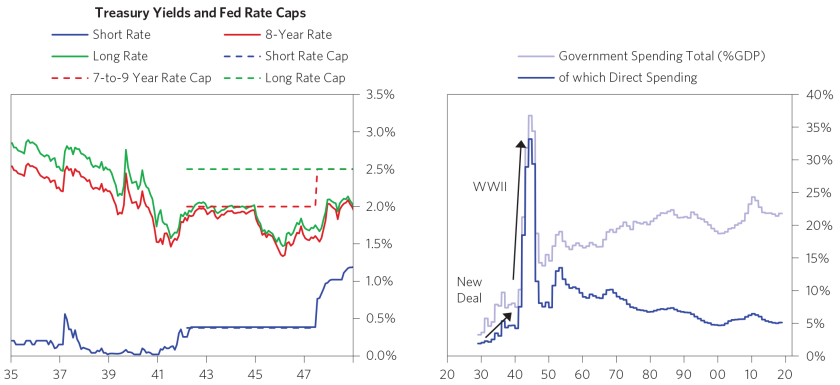

- Central banks will likely lag inflation and push as hard as they can to stimulate economies: We’re likely entering into a period of more managed rates and yield curve targeting, similar to what we saw in the US in the 1940s and early 1950s or what Japan is doing today. A de facto yield curve targeting framework supported by open-ended QE purchases would accommodate a fiscal expansion by preventing increased government issuance from producing an undesirable rise in interest rates.

Next, we recap the key elements of the paradigm shift and highlight the role of the coronavirus as an accelerant.

The Backdrop: High IOUs, Rising Inequality and Political Conflict, and Little Ability to Ease

While the coronavirus shock has rapidly accelerated the shift to the new paradigm, the underlying pressures behind this shift had been building for some time, such that the shift was virtually inevitable at some point. Over the course of the past several decades, a massive wall of IOUs has accumulated in the form of debt, pension benefits, healthcare and social security benefits, etc. These IOUs represent a constant drag on incomes and are too large to be serviced from tax revenue alone. At the same time, central banks already had little ability to ease (low “fuel in the tank”) as interest rates were near zero and quantitative easing had driven down the yields of assets about as far as they could be squeezed. The level of social and political conflict was already at secular highs, driven by growing wealth, income, and opportunity gaps (in part due to QE having disproportionately benefited wealthy asset owners) and their contributions to rising populism.

This confluence of forces, together with inflation persistently below central bank targets, was already pushing policy makers toward greater deficit spending paired with debt monetization. Pairing monetary and fiscal policy is the logical next step for fighting downturns when monetary policy cannot do much more, and it offers an attractive approach for funding IOUs without having to break promises and worsen the social divide. Now, the push is even stronger: central banks are out of bullets, IOUs will grow and are even more unsustainable relative to incomes, and the ongoing downturn has the potential to make conflict even worse.

The Virus Is Producing a Deflationary Shock That Needs to Be Offset

Before the virus hit, global growth was already weak. Now, the response to the virus has produced a massive shock to global incomes that there is an immediate need to offset. We estimate a 6% decline in US GDP and a $4 trillion hit to US company revenues over the course of the year (with a substantial degree of uncertainty around these numbers). If this decline is not offset, it will have long-lasting impacts. We show the US as an example below, but the problem is of course global.

This shock is happening in an environment of secular disinflationary forces like technology, demographics, and globalization that, coupled with weak growth, have resulted in low and stable inflation. Particularly in the context of this shock, secularly low inflation provides both a challenge and an opportunity. It is a challenge because of the risk of deflation and its pernicious effects. With nominal rates already near or below zero in much of the developed world and not able to fall much further, expectations for lower inflation can produce a rise in real yields, causing an undesirable tightening when easing is needed. But low inflation is also an opportunity because excessive inflation is typically the primary constraint on monetary and fiscal policy. With inflation secularly low, policy makers are free to run much easier monetary and fiscal policy than they might otherwise. While real yields have been somewhat disproportionately affected by the recent liquidity squeeze, which clouds the picture a bit, it’s worth noting that 10-year developed world breakeven inflation is now under 1%.

The Move Toward Coordinated Monetary and Fiscal Policy Is Underway

The shock from the virus has pulled forward the need for coordinated monetary and fiscal policy. Monetary policy on its own won’t be able to address the income holes that the virus has opened up. For one thing, monetary policy is already at its limits. Interest rates across the curve are near or below zero throughout the developed world and can’t be lowered much further. And quantitative easing has a weaker impact than it did in the past because asset prices are already relatively high and any further gains would go mostly to the wealthy, who have a lower marginal propensity to spend. Moreover, the root cause of the problem today is a broad gap in incomes that has opened up across the economy, not just a lack of liquidity, and monetary policy on its own will struggle to get money to the broad range of entities that need it.

Fiscal policy has the ability to fill the income gap, but the deficit expansion needed would put upward pressure on interest rates and cause an undesirable monetary tightening at a time when the economy needs easing. Government spending coordinated with money printing (MP3) offers a much more promising path for directly addressing the income hits. Whereas interest rate policy (MP1) works by inducing borrowers to spend, and quantitative easing (MP2) works through its impact on assets and the effects on savers, deficit spending financed by money printing can have a much more targeted impact, as the government can direct the money to where it needs to go. And combining a large fiscal expansion with central bank bond purchases mitigates the upward pressure on long-term interest rates that a large deficit expansion would have, preventing an undesirable crowding out.

We expect to see a move toward policies similar to the Fed’s World War II-era yield curve targeting, where the central bank accommodates a fiscal expansion while ensuring that rates don’t rise into a slowing economy. In order to finance World War II, the Fed capped short-term and long-term interest rates to produce low yields with an upward-sloping yield curve. This allowed the government to run large deficits to fund the war, spending nearly 40% of GDP at peak, without a rise in interest rates. More recently, Japan has pursued a policy of yield curve control that has effectively kept its long-term rates capped.

Policy makers across the developed world are now taking de facto steps toward monetary and fiscal coordination. Most major developed world central banks are now carrying out quantitative easing programs, the US has announced unlimited QE, and Australia has joined Japan in moving toward a yield curve targeting framework. At the same time, governments have begun rolling out fiscal measures. We expect to see more of these programs ahead, in the near term as well as over the next decade, as MP3 increasingly becomes a normal part of policy makers’ tool kits.

Markets Are Discounting That the Steps Taken So Far Won’t Be Enough

Despite the steps taken by policy makers so far, markets are pricing in a substantial risk that the economic weakness from this shock will become self-reinforcing and difficult to reverse, lasting far longer than the virus itself. Markets are discounting a sustained hit to demand, a deep and prolonged shock to earnings, an extended period of disinflationary weakness, and the need to keep interest rates very low over the next decade. All of this underscores the need for the new policy paradigm. Below, we show two perspectives on what’s priced in for earnings—one that draws on equity and bond pricing and one that looks at dividend futures. Both are consistent with a sharp decline in earnings and a slow, protracted recovery.

An Exceptionally Wide Range of Potential Outcomes from Here

We have said that the paradigm shift brings with it a wide range of potential outcomes that have to be considered, including scenarios for which typical portfolios are unprepared. What may have sounded theoretical is now, unfortunately, much more tangible.

Following the global financial crisis and prior to the coronavirus shock, two massive cross-currents were roughly in equilibrium: the secular deleveraging force resulting from high debt levels and weak growth and inflation on the one hand, and the policy response (liquidity production followed by the Trump fiscal stimulus) on the other. This produced a decade of stable economic conditions and strong asset returns. This equilibrium looked precarious to us, with the potential for too much or too little monetary and fiscal response making both a Japan-like depression as well as an inflationary upswing likely enough outcomes to consider.

The shock from the virus has now pushed us significantly down the lower path, with the need for a large and immediate policy response (social, medical, monetary, and fiscal) to prevent us from quickly falling off the cliff. There are still big unknowns with respect to the progression of the virus itself and how societies and medical systems will be able to cope. With respect to the economic impact, we have penciled out a roughly $4 trillion hit to businesses in the US and a global impact of around $12 trillion. The fiscal package announced in the US appears to fill a big part of the gap, making households largely whole but leaving businesses on the hook for a big chunk, roughly $2 trillion, which will need to be met by spending cuts, including capex and financial assets, as well as new borrowing—and if these aren’t enough, default. Longer term, the shift toward MP3, while necessary, carries its own set of risks, with the likelihood of highly divergent outcomes across countries. Policy makers will likely test the limit of monetized deficit spending—the limit being the point at which printing results in currency and/or inflation problems—and different countries will hit that limit sooner than others. Given the dollar’s reserve currency status, the US has more room than others, but that too will eventually be tested.

To us, the near-term risks point to the need for more measured risk-taking for the time being, and both the near-term risks and the broader backdrop of the paradigm shift point to the need for heightened diversification in all forms, as well as stress testing to ensure tolerable outcomes through the full range of potential scenarios.

This research paper is prepared by and is the property of Bridgewater Associates, LP and is circulated for informational and educational purposes only. There is no consideration given to the specific investment needs, objectives or tolerances of any of the recipients. Additionally, Bridgewater’s actual investment positions may, and often will, vary from its conclusions discussed herein based on any number of factors, such as client investment restrictions, portfolio rebalancing and transactions costs, among others. Recipients should consult their own advisors, including tax advisors, before making any investment decision. This report is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy the securities or other instruments mentioned.

Bridgewater research utilizes data and information from public, private and internal sources, including data from actual Bridgewater trades. Sources include the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Capital Economics, CBRE, Inc., CEIC Data Company Ltd., Consensus Economics Inc., Corelogic, Inc., CoStar Realty Information, Inc., CreditSights, Inc., Dealogic LLC, DTCC Data Repository (U.S.), LLC, Ecoanalitica, EPFR Global, Eurasia Group Ltd., European Money Markets Institute – EMMI, Evercore ISI, Factset Research Systems, Inc., The Financial Times Limited, GaveKal Research Ltd., Global Financial Data, Inc., Haver Analytics, Inc., ICE Data Derivatives, IHSMarkit, The Investment Funds Institute of Canada, International Energy Agency, Lombard Street Research, Mergent, Inc., Metals Focus Ltd, Moody’s Analytics, Inc., MSCI, Inc., National Bureau of Economic Research, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Pensions & Investments Research Center, Renwood Realtytrac, LLC, Rystad Energy, Inc., S&P Global Market Intelligence Inc., Sentix Gmbh, Spears & Associates, Inc., State Street Bank and Trust Company, Sun Hung Kai Financial (UK), Refinitiv, Totem Macro, United Nations, US Department of Commerce, Wind Information (Shanghai) Co Ltd, Wood Mackenzie Limited, World Bureau of Metal Statistics, and World Economic Forum. While we consider information from external sources to be reliable, we do not assume responsibility for its accuracy.

The views expressed herein are solely those of Bridgewater as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice. Bridgewater may have a significant financial interest in one or more of the positions and/or securities or derivatives discussed. Those responsible for preparing this report receive compensation based upon various factors, including, among other things, the quality of their work and firm revenues.