The ripple of the banking crisis is one way the tightening will bite into activity and slow growth, cutting some borrowers off from lending and driving a shift in the way consumers and small businesses think about saving.

The problems in the US banking system will ripple through the economy via both direct and indirect channels. Our systematic process works by mapping cause-and-effect linkages through to the outcomes that drive economies and markets. In today’s case, we are in the middle of a rapid tightening cycle, prompted by high inflation. Tightening increases costs for borrowers and incentivizes saving, often continuing until growth slows or something important breaks. Looking forward, we expect the tightening to cause a material slowing in growth as it works through the system (our leading estimate is -2.4% year over year). Typically, the most vulnerable players—those that had grown reliant on cheap capital and abundant liquidity—are exposed first. The cracks in the banking system today are one example, alongside the pockets of weakness that have already emerged, like those in real estate and tech. In this research, we walk through the main ways that the banking stress will have knock-on effects for spending in the economy overall.

- As mentioned in part 2 of this series, the most direct impact will be through disruptions to the supply of credit and a continued tightening of lending standards. Small and other stressed banks provided around 2.7% of GDP (annualized) in lending to the economy over the last three years. This amounted to more than half of the total banking sector lending during that time. These banks are the most likely to tighten credit from here, and that will disproportionately impact some sectors of the economy, where small banks had been the dominant lenders (e.g., VC-backed tech and commercial real estate lending). Large banks and other sources of lending remain in good shape, and there is a viable path to consolidation for weaker banks that are unprofitable or that have mark-to-market capital problems. But as that process is worked through, the flow of credit is likely to be impacted for some time.

- More broadly, this crisis is likely to drive a shift in the way consumers and small businesses view and respond to higher interest rates, which could have larger implications for household and corporate savings rates. The failure of Silicon Valley Bank has highlighted the risks associated with keeping cash in zero-yielding deposit accounts and the relative attractiveness of saving at market rates (via money market funds or T-bills). Higher interest rates incentivize saving (alongside dissuading would-be borrowers), and the dynamic of deposits seeking yield has accelerated meaningfully over the past few months and particularly in the past few weeks. More saving is another way spending could cool from here.

- Finally, the crisis has impacted market discounting of monetary policy and will likely continue to influence bank purchases of bonds for years to come. In the near term, bond yields have fallen rapidly as investors have flocked out of risky assets, and this will provide some offsetting stimulation (e.g., by lowering mortgage rates). But looking further out, banks have been one of the primary buyers of bonds over the last several years, which has helped keep yields and mortgage rates lower. But in the aftermath of this crisis, banks will likely be looking to reduce their duration exposure, possibly amplified by regulation that may come down the pike, reversing their support.

We start by showing the total borrowing by households and businesses in the US, alongside our current and leading reads on activity. We identify stressed banks—a measure of both large banks facing significant strain and small banks. Growth has been resilient to date, even as credit has slowed. The emerging bank strains and their likely pass-through to borrowing and saving should contribute to a broad pullback in activity.

Below, we show the credit pipes through which banks have extended credit to US households and businesses since the pandemic. More than half of the lending had been coming from banks, and much of that from the areas of the banking system that are currently under strain.

The charts below put the direct lending by banks into perspective relative to history and help show how it has evolved. As you can see, in the last year, as credit overall began pulling back, small and stressed institutions continued lending at a strong pace—particularly to businesses and commercial real estate borrowers. Small and stressed banks were particularly significant commercial real estate lenders and had been ramping up lending coming into this period of stress. The largest banks, in contrast, were pulling back from the sector, and the pace of securitization in the commercial mortgage-backed securities market was also slowing. Regional banks snapped up the business. Part of the reason they were able to outcompete the large banks in this segment was that, in 2018, a regulatory rollback exempted banks with $100-250 billion in assets from the Fed’s annual stress tests. In its latest round of these stress tests, the Fed included an extremely harsh scenario for commercial real estate prices (a 40% decline over two years), which likely limited the largest banks’ risk appetite in the space.

For weaker and stressed banks, the likely and least painful path forward is consolidation, which should avert the most disastrous outcome. But even with larger, well-capitalized banks willing to continue lending (albeit at higher standards), some borrowers are likely to struggle to access credit. Many of the businesses served by Silicon Valley Bank and other small banks operate in specialized or concentrated industries and may have a more difficult time demonstrating creditworthiness to bigger lenders who are less familiar with these businesses’ markets or assets.

Higher Interest Rates Have Already Driven a Tightening of Standards and a Decline in the Demand for Credit That Will Likely Worsen from Here

At the end of last year, banks had already begun to tighten credit standards for all borrowers in response to the rapid increase in interest rates. As the charts below illustrate, the greatest degree of tightening of standards occurred in commercial real estate, a sector hit hard first by the pandemic and then by higher interest rates. Now that the cheap deposit funding enjoyed by small banks is at risk of moving elsewhere and bank exposure to risky assets is being heavily watched, it is likely that a further tightening of standards is ahead of us. At the same time, higher interest rates have also driven a pullback in borrowing as businesses and consumers are dissuaded by high borrowing costs.

Changes to How Households and Businesses Perceive Bank Risk and the Attractiveness of Saving Have the Potential to Drive a Broader Pivot Toward Saving

Higher interest rates also make saving more attractive relative to spending, as cash can earn a higher return. Until recently, banks were largely paying well below the cash rate on deposits and were seen as the main, or only, option for where to keep cash. As consumers reassess their willingness to keep their deposits in low-earning accounts and concerns about financial stability mount, this may ripple through to decisions about how much to pull back from spending to save. The chart below shows the household savings rate, which remains near historical lows.

As the charts below show, demand for money market funds and T-bills has been picking up rapidly over the last several months, and households and other players have been moving cash to capitalize on the increase in the cash rate. The timeliest inflows into money market funds show that the move out of deposits is still ongoing. These point to some households and businesses responding to higher interest rates but, as reflected in the perspective above, haven’t yet been enough to materially impact spending decisions so far.

Markets Are Now Pricing That the Banking Crisis Will Be Enough to Cause an Easing by June

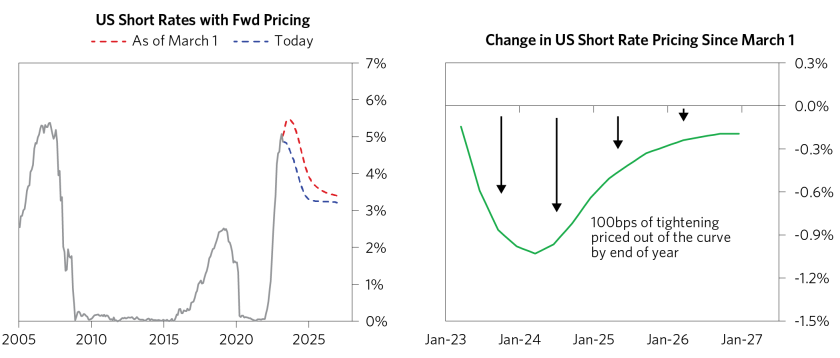

The crisis has also brought about an immediate material shift in the forward discounting of monetary policy. Today, almost 100bps of tightening have come out of the short rate curve since the beginning of March. In the near term, this price action is stimulative as lower interest rates bring down the costs following borrowers. But this price action likely under-reflects the degree to which the Fed remains constrained by inflation. Without more evidence of a larger hit to activity, above-target inflation remains a constraint, just as causing further financial instability presents a challenge to setting policy too tight.

This research paper is prepared by and is the property of Bridgewater Associates, LP and is circulated for informational and educational purposes only. There is no consideration given to the specific investment needs, objectives, or tolerances of any of the recipients. Additionally, Bridgewater's actual investment positions may, and often will, vary from its conclusions discussed herein based on any number of factors, such as client investment restrictions, portfolio rebalancing and transactions costs, among others. Recipients should consult their own advisors, including tax advisors, before making any investment decision. This material is for informational and educational purposes only and is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy the securities or other instruments mentioned. Any such offering will be made pursuant to a definitive offering memorandum. This material does not constitute a personal recommendation or take into account the particular investment objectives, financial situations, or needs of individual investors which are necessary considerations before making any investment decision. Investors should consider whether any advice or recommendation in this research is suitable for their particular circumstances and, where appropriate, seek professional advice, including legal, tax, accounting, investment, or other advice.

The information provided herein is not intended to provide a sufficient basis on which to make an investment decision and investment decisions should not be based on simulated, hypothetical, or illustrative information that have inherent limitations. Unlike an actual performance record simulated or hypothetical results do not represent actual trading or the actual costs of management and may have under or over compensated for the impact of certain market risk factors. Bridgewater makes no representation that any account will or is likely to achieve returns similar to those shown. The price and value of the investments referred to in this research and the income therefrom may fluctuate. Every investment involves risk and in volatile or uncertain market conditions, significant variations in the value or return on that investment may occur. Investments in hedge funds are complex, speculative and carry a high degree of risk, including the risk of a complete loss of an investor’s entire investment. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a complete loss of original capital may occur. Certain transactions, including those involving leverage, futures, options, and other derivatives, give rise to substantial risk and are not suitable for all investors. Fluctuations in exchange rates could have material adverse effects on the value or price of, or income derived from, certain investments.

Bridgewater research utilizes data and information from public, private, and internal sources, including data from actual Bridgewater trades. Sources include BCA, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Bond Radar, Candeal, Calderwood, CBRE, Inc., CEIC Data Company Ltd., Clarus Financial Technology, Conference Board of Canada, Consensus Economics Inc., Corelogic, Inc., Cornerstone Macro, Dealogic, DTCC Data Repository, Ecoanalitica, Empirical Research Partners, Entis (Axioma Qontigo), EPFR Global, ESG Book, Eurasia Group, Evercore ISI, FactSet Research Systems, The Financial Times Limited, FINRA, GaveKal Research Ltd., Global Financial Data, Inc., Harvard Business Review, Haver Analytics, Inc., Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), The Investment Funds Institute of Canada, ICE Data, ICE Derived Data (UK), Investment Company Institute, International Institute of Finance, JP Morgan, JSTA Advisors, MarketAxess, Medley Global Advisors, Metals Focus Ltd, Moody’s ESG Solutions, MSCI, Inc., National Bureau of Economic Research, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Pensions & Investments Research Center, Refinitiv, Rhodium Group, RP Data, Rubinson Research, Rystad Energy, S&P Global Market Intelligence, Sentix Gmbh, Shanghai Wind Information, Sustainalytics, Swaps Monitor, Totem Macro, Tradeweb, United Nations, US Department of Commerce, Verisk Maplecroft, Visible Alpha, Wells Bay, Wind Financial Information LLC, Wood Mackenzie Limited, World Bureau of Metal Statistics, World Economic Forum, YieldBook. While we consider information from external sources to be reliable, we do not assume responsibility for its accuracy.

This information is not directed at or intended for distribution to or use by any person or entity located in any jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability, or use would be contrary to applicable law or regulation, or which would subject Bridgewater to any registration or licensing requirements within such jurisdiction. No part of this material may be (i) copied, photocopied, or duplicated in any form by any means or (ii) redistributed without the prior written consent of Bridgewater® Associates, LP.

The views expressed herein are solely those of Bridgewater as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice. Bridgewater may have a significant financial interest in one or more of the positions and/or securities or derivatives discussed. Those responsible for preparing this report receive compensation based upon various factors, including, among other things, the quality of their work and firm revenues.