With central banks on the verge of achieving their goals—supporting stability, profits, and asset prices—global political shifts risk upsetting the balance.

After five years of severe imbalances, global economies are converging on a reasonable state of equilibrium, a condition that is generally good for assets. Developed world central banks, including the Fed, are responding to the stabilization of conditions within tolerable ranges by gradually cutting rates toward what they view as a neutral posture. Meanwhile, China, which has been a deflationary outlier over this period, has begun to recognize the problem and is prioritizing boosting domestic demand, even if the policies are not yet clearly defined. And AI technology has advanced to show real potential to enhance productivity over time. If these were the only developments in the world, you should expect an era of stability and strong profits. That’s what markets are discounting and what is therefore required to generate a strong positive return, particularly for US equity indexes, which are pricing an even more exceptional decade than the last.

Enter President-elect Trump and a team of aggressive interventionists. What will their policies be? What will be the impacts? We can assume that the bias will be pro-growth and pro-business, but the uncertainties are high. In the US, imposing tariffs on imports, restricting immigration, and keeping the fiscal pipe open are likely to challenge the Fed’s ability to achieve the goals that they have not quite achieved. Outside the US, the risks tilt to the downside, particularly in external-surplus economies like China and Europe, which have been the most reliant on the existing global trade system.

This political turn of events now fully entrenches a shift in the global world order from free-market globalization to mercantilism. Mercantilism is government’s response to local populations whose dissatisfaction with their circumstances calls for governments to do something about it. This call to action is reinforced by the learnings that fiscal and industrial policy can be powerful tools, having reversed severe economic downturns in the US and Europe and supported the rapid development of dominant industries in China. A mercantilist consensus is now deeply established in the US, but US policy makers are less experienced with it. In China, policy makers have experience with the approach but have mainly used it to stimulate supply rather than demand. Europe threatens to be left behind due to weak central policy making and the competition it now faces on two fronts. Across the world, the risk of tit-for-tat escalation in mercantilist competition (and of broader conflict) threatens the path to equilibrium.

A template is needed to assess this combination of actual and discounted economic stability on the one hand, and geopolitical instability on the other, as well as the implications for investors. Our template views the economy as a sum of spending transactions driven by three big forces: productivity, the long-term debt cycle, and the short-term debt cycle. The operation of these forces is mediated by policy levers (monetary and fiscal) as policy makers vie for a sustainable equilibrium. And asset returns depend on how these economic conditions transpire in relation to what was discounted.

In terms of what we see as we apply this template across the world today:

In the US: Short-term cyclical dynamics are sustaining nominal spending at too-high levels, while the advent of mercantilist policy (e.g., tariffs, targeted fiscal measures, restrictions on immigration, stimulus in China) tilts the risks of inflation higher. To “have it all” (i.e., the currently discounted mixture of high profits, low inflation, high wage growth, and easing) against this backdrop requires sustained, high productivity growth, which an AI revolution makes possible but does not ensure. From a long-term debt cycle perspective, debt burdens have shifted from the private to the public sector and are once again manageable via interest rate cuts, leaving us in an interesting configuration where monetary easing and private credit creation can support growth, but the sustainability of fiscal spending is in question.

In China: Deflationary pressures from the long-term debt cycle are weighing on credit growth, leading to very weak nominal spending, which is too low by about half. Stimulus is needed to transition from what is now an ugly deleveraging, which is good for bonds but bad for just about everything else, to a beautiful deleveraging that stabilizes conditions and supports a movement of money from cash to assets. China has endured years of deleveraging because, in contrast to the US, it did not monetize unsustainable private and local government debts; instead, it used mercantilist production-side stimulus to support healthy industries and national champions. But now signs are emerging of more proactive central government fiscal support, which is needed more than ever as proposed tariffs threaten China’s export-driven growth model. Almost any stimulus is likely to support Chinese assets, as its stocks are discounting a depression and bonds are not discounting much easing. Exactly which assets will benefit, as well as the ripple effects for global spending, will depend on the effectiveness of policy choices.

Europe remains in a state of long-term stagnation, losing the productivity and tech battle to the US and the manufacturing battle to China. While real growth looks stable around potential as ECB easing pumps growth into the periphery, replacing declining fiscal support, European powerhouses Germany and France face export stagnation and debt challenges, respectively. The risks to economic growth are tilted downward as we pencil out the likely impact of tariffs on the bloc and the challenges faced by Europe’s weak central institutions in formulating a domestic fiscal or international mercantilist response.

In terms of what this means for investors:

Diversification is crucial as markets are pricing certainty connected to stable economic conditions, whereas uncertainty is high and rising for the reasons described above. The forms of diversification that look most important include balancing exposure between economic growth and inflation, as the threats are in both directions; another is geographic diversification, which can take advantage of the decline in country correlations that results from mercantilism.

It’s more important to pick and choose the assets that are most appropriate to the conditions and your goals rather than relying on static weights or the market-cap portfolio, given the range of possible outcomes and how concentrated most institutional allocations and the market cap-portfolio have become.

For long-only allocators, the environment favors assets relative to cash, stocks versus bonds, and the US dollar in the near term, reflecting stable conditions, high and sustainable nominal growth, and US strength.

True alpha and diversifying alpha are exceedingly valuable, and most investors could use as much as they can find.

We describe these dynamics below in more detail.

Our Template

Our starting point to assess conditions and asset pricing is to recognize that an economy is simply a sum of transactions—exchanges of money for quantity, financed by money, credit, and income. These transactions culminate in three broad economic forces—productivity, a long-term credit cycle, and a short-term credit cycle or business cycle—which impact the cause/effect linkages of the system and the pulling of the monetary and fiscal policy levers to achieve the desired conditions.

To describe the three big forces:

- Productivity Growth: increases in know-how and permanent capital stock. Productivity growth increases the economy’s real wealth and raises the quantity of goods and services that can be produced from a given supply of labor and capital (and by extension the level of spending that can be absorbed without creating inflationary imbalances).

- The Long-Term Debt Cycle: the process by which economy-wide debt burdens rise or fall over decades, influencing the potential for longer-term growth through the expansion of credit, creating or consuming potential growth, and varying the degree to which conventional policies can effectively manage current economic conditions. When unconventional policy is required to drive down debt burdens relative to incomes, we typically see big impacts on the path of conditions and asset markets.

- The Short-Term Debt Cycle: normal fluctuations in nominal spending, growth, and inflation driven by the expansion and contraction of money and credit as policy makers pull the levers available to them to keep conditions in sustainable equilibriums (i.e., spending in line with output, debts in line with income, and normal risk premiums on assets in relation to cash).

Policy makers have two main levers to navigate the interaction of these forces: monetary policy and fiscal policy (including macroprudential policies). In pulling these levers, policy makers’ aims are to keep conditions in sustainable equilibrium and to avoid limits that would make the status quo unsustainable, like deflation, inflation, bubbles, or currency weakness.

A unique feature of the environment today is that all three forces are highly relevant to what conditions look like and how they are likely to evolve, while each of the policy levers and their combinations are in play.

In terms of how recent developments fit into this template:

Globally

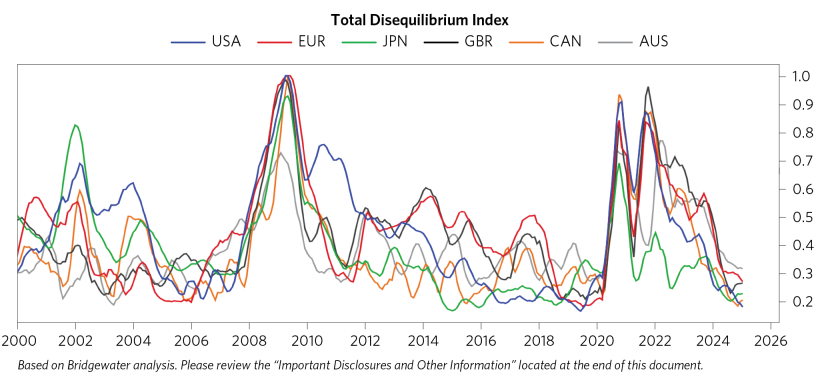

Most developed economies have moved closer to short-term debt cycle equilibrium, which is typically supportive of stable economic activity and asset returns. Following COVID, economies were well out of equilibrium. Incomes collapsed, interest rates hit 0%, and fiscal policy stimulation more than offset the collapse in incomes, creating inflationary imbalances. Central banks tightened to manage these, decreasing the compensation on offer in assets relative to cash without immediately solving inflationary problems. Given this configuration, about 18 months ago, only a handful of major economies were in what we would call sustainable equilibrium conditions. Eventually, the tightening drove down credit creation, which, coupled with strong productivity growth, brought spending in line with output. This facilitated disinflation and enabled central banks to shift toward easing, restoring a discounted risk premium in assets versus cash. This sequence brings us toward sustainable equilibriums across most developed economies, including the US. Environments like these are typically supportive to assets broadly, as the falling return on cash drives investors out the risk curve and stability encourages economic activity. The chart below puts the big movements into perspective, showing how far we’ve come over the past two years.

The way policy makers will use their levers to manage the cycle going forward is evolving, given the crystallizing trend of mercantilist policy. Mercantilism is fiscal policy, applied not with a focus on broad growth but on national security, self-reliance, and on the composition of economic growth rather than its level (e.g., manufacturing being important for certain kinds of jobs, winning the tech race). The most obvious example is tariffs, but mercantilism applies more broadly to measures aimed at avoiding trade deficits, bolstering self-reliance in key industries, and protecting national champions. The key implications of mercantilism within our template include: some headwinds to productivity growth given the impacts of uncertainty on long-term capital formation, upward pressure on cyclical inflation in the short-term debt cycle from measures like tariffs and restrictions on immigration (which has been an important driver of labor supply growth), and increased salience of fiscal policy for individual company performance and profits. More generally, mercantilism introduces policy incentives and effects that need to be understood by investors in much the same way as traditional monetary and fiscal measures, as well as the risk of cascading tit-for-tat measures that need to be accounted for in assessing the potential paths of conditions and asset pricing.

Applying our template across major economies, in light of these developments:

The US

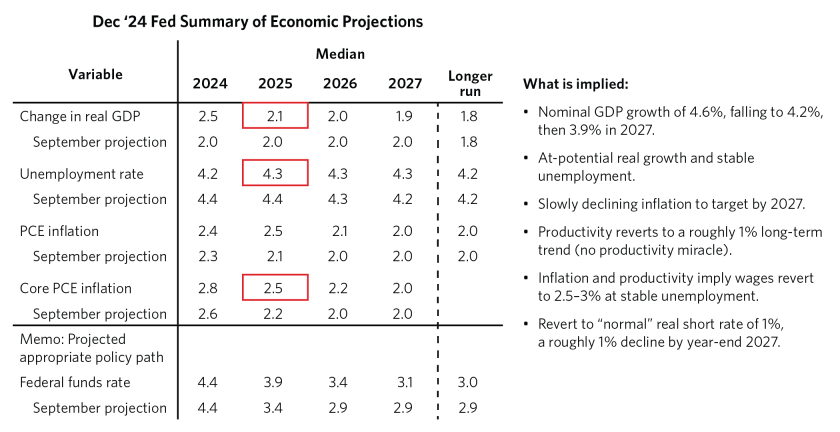

In the US, the cycle is self-sustaining at a somewhat higher level of nominal spending than the Fed has laid out. The Fed expressed their expectations for future conditions in their quarterly summary of economic projections, shared below. We find this more useful than their dot plot because it describes, in an “if, then” way, the conditions compatible with their plans to bring short-term interest rates to a given level. In December, the Fed shifted up their projections for growth, inflation, and rates by the end of 2025: they are now projecting a move to a short-term interest rate of 3.9% given nominal spending of 4.6%, with real growth stabilizing around potential at 2.1%, inflation at 2.5%, and a slight increase in unemployment.

This is an interesting projection because it implies lower real growth and wages without a clear impetus to get there. The Fed’s 2.1% real growth assumption for 2025 implies productivity growth of not more than ~1%, which, looking at sources and uses of spending, would make their inflation target compatible with wages around 2.5% to 3% but not higher. To square the Fed’s assumption, we’d need to see a decline in wages without much labor market weakening. But by our measures, growth and its components are sustainably higher than the Fed’s projections, with nominal spending currently running a bit above 5%, supported by wages around 4%—which is generating inflation of a bit above 2.5%, and then only because high productivity growth sustained around 2% has absorbed inflationary pressure. And the labor market is tightening rather than softening as the Fed is projecting, since strong coincident demand financed by incomes is pulling up employment (compared to this summer, when labor market easing pulled employment down), as shown in the chart below.

On top of this, we see several drivers of spending where the balance of probabilities is tilted toward higher rather than lower nominal spending going forward:

- Do Trump’s policies accelerate nominal spending? Looking ahead, there is a question as to how far and fast private sector balance sheets relever in response to the short rate easing, adding to the flow of spending. There are also the spending impacts of President-elect Trump’s proactive and mercantilist policy agenda, notably through the fiscal lever (where a united Republican Congress increases the odds of stimulus measures) and through the incoming administration’s tariff proposals. For now, we are penciling in a mild boost to US spending, although there is a range related to the specific policies that are announced. (Our research describes in more detail how we are assessing the impacts of Trump policy.)

- Does productivity growth normalize, keeping spending at high levels? High wage growth and strong profits are challenging to sustain without inflation, because they produce high spending growth. The US “got it all” (i.e., high wages, spending, and disinflation) over the past several months because a surge in non-inflationary sources of supply effectively absorbed inflationary pressure. The question is, can that be sustained? On the one hand, we typically see productivity and labor force growth revert following such large gains, because the underlying dynamics (e.g., the shifting composition of employment post-COVID, workers coming off the sidelines) only have so much room to run. On the other hand, we could also be on the precipice of an AI revolution that structurally raises productivity in the US, pushing back inflationary limits. When we net these pressures today, we expect we will see some cyclical normalization of productivity well before AI’s productivity benefits come online. Realizing the real benefits of this tech is likely to take time and capex that pushes wages up, not down, in the short term, as we’ve described in our AI research.

- Will China continue to be a deflationary force? Looking back, low nominal growth and supply-side stimulus in China have produced deflation, which has had ripple effects globally. If China begins to stimulate more meaningfully, a pickup in Chinese demand in response to fiscal and monetary stimulus could reverse some of this deflationary impulse. When we track China’s progress against its secular deleveraging goals and assess both the forward policy intent and the impacts of the stimulus that has been announced, China’s deflationary influence is likely to be reduced.

Stepping back to a long-term debt cycle perspective: debts have shifted from the private to the public sector, changing the channels for stimulus and the impact of government borrowing looking ahead. The aggressive MP3 policy mix deployed post-COVID radically improved private balance sheets, both via transfers and because the self-reinforcing cycle of rising spending and wages they kicked off kept incomes and growth strong throughout the recent tightening cycle, replacing collapsing private credit creation. The cost of achieving this good growth outcome was a rise in inflation (which was dealt with via tightening) and a rapid rise in public sector debts. That leaves us in an interesting configuration: households and businesses are not too indebted, and they can support an expansion by borrowing as rates fall. But the public sector is indebted, raising the question of the sustainability of public debts and the government’s current fiscal stance (a topic we cover in more detail in the linked research). Given proactive fiscal policy, government borrowing is now positively aligned with private sector credit growth, which increases the risk of rising total debts, interest rates, and inflation when policy makers increase fiscal spending.

In terms of policy tools to navigate future downturns: monetary and fiscal policy are both available but are about one bad cycle away from exhaustion. From a standing start, there is no particular limit on either monetary policy or fiscal policy, but once they are utilized over time in one way or another, limits can be reached in terms of their usability. After 30 years of cutting interest rates from 1980 to 2010, the ability to use interest rates to stimulate in the US and other economies reached its limits because debt burdens were too high and rates hit 0%. That required a shift to what we refer to as MP2, i.e., QE, which during the pandemic by and large reached the limits of its effectiveness to stimulate growth. That led to the need for MP3 and fiscal policy to reflate the economy post-pandemic, which hit initial limits in the form of inflation and which, due to the expansion of government debts, are pulling forward the future limits of government debt sustainability. The good news is that the rise in interest rates that was required to fight inflation gives the US room to ease through interest rates again, and healthy private sector balance sheets may be more responsive to that easing than pre-COVID. But we are essentially one big easing cycle away from rates being back at zero. If at that stage fiscal sustainability becomes an issue, then, depending on the severity of the issues to be managed, a future downturn could require more drastic steps than fiscal stimulus, such as debt or monetary restructuring, to get the desired results.

In any configuration of future conditions, US assets face a significant hurdle to sustain outperformance. On an outright basis, the backdrop of easing, strong growth, and limited inflation is positive for US assets. What is more challenging is for US assets to repeat a decade of outperformance like they have just experienced. At their current level of global market capitalization, US stocks need to attract ~65 cents of every dollar that flows into stocks just to keep rising. And the pricing sets a high hurdle for these flows: in 2010, US earnings were discounted to grow modestly and at a similar rate to the rest of the world. The US then had an exceptional decade because its companies were more dynamic, had more supportive governance for shareholders, and operated against a more favorable policy backdrop. That’s all still true, but it’s also the case that US equity indexes and bond markets are extrapolating very fast earnings growth outright and versus the rest of the world, as well as stable inflation. The outcome that could square this challenge would be if the US captures the lion’s share of benefits of the AI revolution over time, both pushing back its structural inflationary limits via sustained high productivity and driving substantial profit growth. That outcome is possible but far from assured, and we’re tracking it closely in our AI research.

China

China is still working through a long-term debt cycle deleveraging, and it’s ugly. China’s private sector and local governments are over-indebted, choking off growth. The interest rate lever by itself is not enough to drive spending sustainably above debt service, both because the burdens are large relative to incomes and because lowering rates may have undesirable consequences, such as increasing debt growth in the real estate sector or putting pressure on the renminbi. Most stimulus to date has come through “targeted” fiscal measures aimed at raising industrial production rather than broad demand, in view of the challenges above as well as policy makers’ stated desire to shift the composition of growth toward higher-value-add “new economy” sectors. The effect of this policy has been to capture manufacturing share from the rest of the world and raise political ire, but not to pull China out of its deflationary rut. The good news is that China’s central government, unlike its private sector and local governments, is not indebted, and policy makers have the ability to stimulate through that channel if there is the will to do so.

Nominal spending in China has been too low by half, necessitating more stimulation. China needs roughly 6-7% nominal spending growth but has been running nominal spending around 3.5%. That nets growth around 4% with intolerable deflation that is making economic problems worse, especially in the indebted real estate sector and by hurting corporate profits and sentiment, resulting in a self-reinforcing downward spiral. The path forward to sustained 6-7% nominal growth (i.e., the 5% real growth target plus acceptable inflation) is undefined at this point. But recently, the central government has made commitments to take additional steps to stimulate broad demand. It hasn’t said it will do “whatever it takes” to generate growth, although that is what is implied, and we’re tracking the scale and mechanics of stimulus announcements closely.

However policy makers choose to proceed, it is likely to be supportive for Chinese assets. In studying dozens of reflations across hundreds of years, we see that policy makers tend to get the conditions they want, and that getting there requires making assets attractive relative to cash. But which assets will do well over what timescale depends on the policy mix and the resulting economic conditions. In the US, the “beautiful deleveraging” policy mix used since 2008 created demand through a combination of monetary easing, QE, and fiscal stimulus. It was pro-growth without being too inflationary, contributing to an extraordinary rise in the stock market. In China, the approach of relatively restrained macroprudential policy, targeted fiscal policy, and some liquidity provision since COVID has resulted in low growth, grinding disinflation, and a substantial decline in the stock market but a huge bond rally. Looking forward, both Chinese stocks (which are discounting a depression) and Chinese bonds have the potential to benefit if policy makers stimulate vigorously.

Europe

Europe risks stagnation unless it can better manage political constraints on economic policy. Europe’s deleveraging from the sovereign debt crisis depended on the strength of core economies like Germany and France, which benefited from export growth and increased fiscal spending, and ECB support to offset weakness in periphery countries and austerity throughout much of the bloc. Today, those conditions have turned on their head: growth in Europe’s periphery is moderate, but European conditions are weak overall because German exports have stagnated in the face of Chinese competition and France faces a debt reckoning. The ECB’s recent tightening cycle and Germany’s low government debt levels should in theory give policy makers room to maneuver and stimulate. But rapid, game-changing stimulus is unlikely given political constraints: at the country level, Germany has to contend with fractious politics and its “debt brake.” At the EU level, there is not enough pain to generate the political will that would be needed to reconsider the Stability and Growth Pact. The net of this: there is more inertia in Europe for events to take their course without meaningful policy intervention. That is worsening the dislocations that lost Europe the productivity battle to the US and the manufacturing battle to China over the last 10 years. The challenges created by this lack of coordinated policy making are worsening as global policy takes on a more mercantilist character and Europe faces industrial policy challenges from the US in addition to those it is already managing with China.

Europe has not yet achieved its inflation goals and it may be challenging to ease as aggressively as is discounted, though the risks to spending are tilted to the downside. The pressures Europe is balancing are drags from the roll-off of pandemic-era fiscal spending, Germany’s export competitiveness challenges, and France’s debt challenges, versus green shoots of a private sector response to easing, notably in peripheral Europe. Today, nominal spending is around 4%, and low productivity means that a high share of that spending is translating to inflation (around 3%), with real growth around potential of 1%. Markets are discounting that short rates will come down ~100bps over the next year, ending 2025 with rates about 100bps lower than was discounted midyear. When we add up the pressures, we see this priced-in easing as marginally aggressive for countries like Spain and Italy and therefore unlikely to proceed quite as quickly as discounted unless we see further progress on wages and inflation—but at the same time probably not enough to revive economies like Germany suffering from a manufacturing recession, keeping overall growth and wages roughly steady. Unlike in the US, the balance of risks to nominal spending is tilted downward, notably due to the impact of likely Trump tariffs on the bloc.

What Does All This Mean for Investors?

From a strategic perspective, this environment argues for quality diversification. One dimension is diversification across the range of possible growth and inflation outcomes. If the shift to easing extends the cycle by spurring higher private sector borrowing, we could get even higher nominal growth than discounted. Conflict or trade wars, on the other hand, could drive spending down relative to benign pricing. Second, there is diversification across geography: the fragmentation of global trading blocs in response to geopolitical conflict and the pursuit of mercantilism has the effect of reducing the correlation of economic conditions and market movements around the world. That offers the free benefit of global diversification—we’d take it, particularly as competitive dynamics increase the chance that there will be clear winners and losers. A third dimension is between currencies and other storeholds of value (e.g., gold and commodities) given the potential for continued monetized deficit spending at much higher levels of government indebtedness, and as conflict raises the risks entailed by saving in foreign reserve assets. Finally, in a world of rising conflict, it’s prudent to consider geopolitical alignment. In our studies, it tends to be the case that neutral countries do relatively well through conflicts, while the losers do the worst for obvious reasons and the winners tend to be a mixed bag, given the cost of waging even winning conflicts.

More generally, this is an environment where you need to pick and choose the assets that are most appropriate to the conditions and your goals. A static asset allocation mix and market-cap portfolio are low-cost and efficient to implement, but relative to history most institutional allocations and the market capitalization portfolio are more concentrated than they have ever been (the largest recipients of capital being a handful of US companies, and the US government being the biggest debtor). At the same time, the pricing of those assets is as optimistic as it has been and the range of outcomes relating to more secular forces is extremely wide. This is an environment where we expect that moving away from benchmarks to pick the securities and assets that can benefit from the environment or that are diversifying or safe will yield benefits. As an example, consider the US equity index: large-cap stocks are discounting optimistic earnings growth across the board, but under the hood, nominal growth looks very different by area—e.g., roughly 2% in goods, 7% in services—and each company has varied exposures to foreign operations and sales, meaning their earnings are very differently affected by tariffs and the international policy responses to them. In this environment, we’d tilt toward the equities that can earn the steady elements of US nominal growth and are not exposed to these challenges, rather than the similarly priced equities that are exposed to weaker growth and more uncertainty.

In terms of how we would allocate given these macro conditions and a long-only allocation: we would tilt toward assets versus cash, stocks versus bonds, and the US dollar relative to other currencies.

- We find it useful to separate the decisions of which countries, which assets, and which currencies are most attractive to hold, because the drivers are different in each case. When we talk about which countries are most attractive, we are thinking in terms of a balanced mix of assets relative to cash because that most clearly isolates the level of risk premiums available to collect whether growth or inflation end up above or below what was discounted. We assess which assets are most attractive to tilt toward based on the likely paths of growth and inflation and the environmental biases of different assets relative to those. Which currencies to hold is an independent decision. Often, when policy makers make assets attractive to hold it also makes the currency unattractive to hold, because the way to make assets attractive is to devalue cash.

- Looking across these decisions, today we’re around target risk in a global balanced portfolio across countries that are priced to ease and are able to do so, and that face relatively stable conditions (e.g., the US, the UK, Canada), as well as countries with substantial easing pressure (e.g., China). Within the developed world, we favor stocks in relation to bonds at a comparable level of risk because we’re in an environment that is sustainable around equilibrium: we have a strong economy with inflation in check but some degree of risk to the upside that supports corporate profits but results in tighter policy on the margin. We still see the dollar as attractive despite US indebtedness, given the notable strength in US conditions compared to other developed economies.

Looking ahead, we are in a macro environment in which true alpha is essential and environmental biases should be recognized and managed. Dynamics that were muted for the decade pre-COVID—such as inflation, interest rate volatility, currency volatility, and shifts in monetary and fiscal policy paths—are now crucial drivers of market outcomes, which can have favorable or unfavorable impacts depending on one’s environmental biases. Mercantilism raises the uncertainty of macro conditions on market outcomes, while markets, which are coming off one of the best decades in history, continue to price certainty, and investors are as concentrated as they ever have been in the assets that did well. This setup raises the value of true, uncorrelated alpha that adds diversifying return to portfolios. It also raises the value of alpha and beta strategies that improve portfolio resilience by reducing environmental bias. We see this most notably in areas where investors have stopped looking—for example, in fixed income, where allocations are about as small as they have ever been despite the diversifying potential of such allocations. We also see it in the ability to engineer alpha strategies that are complementary to asset portfolios by tactically reducing environmental biases.

© 2025 Bridgewater® Associates, LP. By receiving or reviewing this material, you agree that this material is confidential intellectual property of Bridgewater® Associates, LP and that you will not directly or indirectly copy, modify, recast, publish or redistribute this material and the information therein, in whole or in part, or otherwise make any commercial use of this material without Bridgewater’s prior written consent. All rights reserved.

This research paper is prepared by and is the property of Bridgewater Associates, LP and is circulated for informational and educational purposes only. There is no consideration given to the specific investment needs, objectives or tolerances of any of the recipients. Additionally, Bridgewater's actual investment positions may, and often will, vary from its conclusions discussed herein based on any number of factors, such as client investment restrictions, portfolio rebalancing and transactions costs, among others. Recipients should consult their own advisors, including tax advisors, before making any investment decision. This material is for informational and educational purposes only and is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy the securities or other instruments mentioned. Any such offering will be made pursuant to a definitive offering memorandum. This material does not constitute a personal recommendation or take into account the particular investment objectives, financial situations, or needs of individual investors which are necessary considerations before making any investment decision. Investors should consider whether any advice or recommendation in this research is suitable for their particular circumstances and, where appropriate, seek professional advice, including legal, tax, accounting, investment or other advice. No discussion with respect to specific companies should be considered a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular investment. The companies discussed should not be taken to represent holdings in any Bridgewater strategy. It should not be assumed that any of the companies discussed were or will be profitable, or that recommendations made in the future will be profitable.

The information provided herein is not intended to provide a sufficient basis on which to make an investment decision and investment decisions should not be based on simulated, hypothetical or illustrative information that have inherent limitations. Unlike an actual performance record simulated or hypothetical results do not represent actual trading or the actual costs of management and may have under or over compensated for the impact of certain market risk factors. Bridgewater makes no representation that any account will or is likely to achieve returns similar to those shown. The price and value of the investments referred to in this research and the income therefrom may fluctuate. Every investment involves risk and in volatile or uncertain market conditions, significant variations in the value or return on that investment may occur. Investments in hedge funds are complex, speculative and carry a high degree of risk, including the risk of a complete loss of an investor’s entire investment. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a complete loss of original capital may occur. Certain transactions, including those involving leverage, futures, options, and other derivatives, give rise to substantial risk and are not suitable for all investors. Fluctuations in exchange rates could have material adverse effects on the value or price of, or income derived from, certain investments.

Bridgewater research utilizes data and information from public, private, and internal sources, including data from actual Bridgewater trades. Sources include BCA, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Bond Radar, Candeal, CBRE, Inc., CEIC Data Company Ltd., China Bull Research, Clarus Financial Technology, CLS Processing Solutions, Conference Board of Canada, Consensus Economics Inc., DataYes Inc, DTCC Data Repository, Ecoanalitica, Empirical Research Partners, Entis (Axioma Qontigo Simcorp), EPFR Global, Eurasia Group, Evercore ISI, FactSet Research Systems, Fastmarkets Global Limited, The Financial Times Limited, FINRA, GaveKal Research Ltd., Global Financial Data, GlobalSource Partners, Harvard Business Review, Haver Analytics, Inc., Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), The Investment Funds Institute of Canada, ICE Derived Data (UK), Investment Company Institute, International Institute of Finance, JP Morgan, JSTA Advisors, LSEG Data and Analytics, MarketAxess, Medley Global Advisors (Energy Aspects Corp), Metals Focus Ltd, MSCI, Inc., National Bureau of Economic Research, Neudata, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Pensions & Investments Research Center, Pitchbook, Rhodium Group, RP Data, Rubinson Research, Rystad Energy, S&P Global Market Intelligence, Scientific Infra/EDHEC, Sentix GmbH, Shanghai Metals Market, Shanghai Wind Information, Smart Insider Ltd., Sustainalytics, Swaps Monitor, Tradeweb, United Nations, US Department of Commerce, Verisk Maplecroft, Visible Alpha, Wells Bay, Wind Financial Information LLC, With Intelligence, Wood Mackenzie Limited, World Bureau of Metal Statistics, World Economic Forum, and YieldBook. While we consider information from external sources to be reliable, we do not assume responsibility for its accuracy.

This information is not directed at or intended for distribution to or use by any person or entity located in any jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to applicable law or regulation or which would subject Bridgewater to any registration or licensing requirements within such jurisdiction. No part of this material may be (i) copied, photocopied or duplicated in any form by any means or (ii) redistributed without the prior written consent of Bridgewater ® Associates, LP.

The views expressed herein are solely those of Bridgewater as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice. Bridgewater may have a significant financial interest in one or more of the positions and/or securities or derivatives discussed. Those responsible for preparing this report receive compensation based upon various factors, including, among other things, the quality of their work and firm revenues.