As most major economies are seeing their working-age populations stagnate or shrink, sub-Saharan Africa’s is growing rapidly and projected to be larger than China’s in about a decade. If the region can also increase its productivity growth, it will begin to emerge out of poverty and gradually become relevant to global investors.

The forces that shape the world over decades are very different than those that make headlines from day to day, and these secular dynamics—while slow-moving—are often some of the most impactful. The slowing, and in some cases outright shrinking, of population growth in the industrialized world is one of these long-term forces that will gradually remake the shape of the global economy. But this demographic trajectory is not the same everywhere. The population is declining in some places while growing rapidly in others.

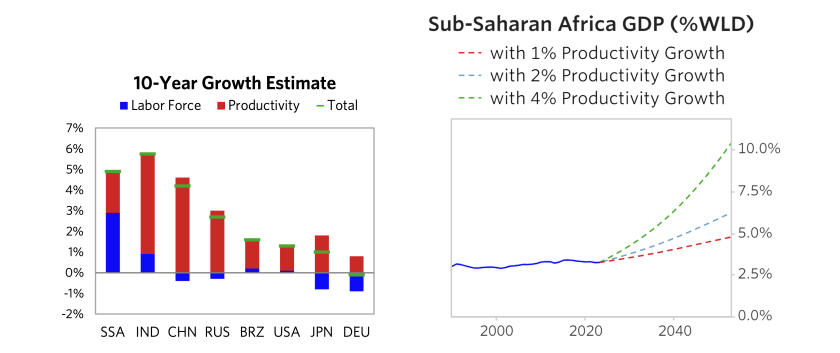

Most notably, sub-Saharan Africa’s population is booming. It is projected to account for a quarter of the world’s working-age population within a few decades and have more people of working age than China in about 10 years. This means that even if productivity growth is modest, sub-Saharan Africa is on track to be one of the fastest-growing areas in the world, and its role in the global economy, which is very small today (3% of global GDP across about 40 countries with little integration into key supply chains), will likely increase as well.

In this report, we examine this secular pressure and pencil out how meaningful the growth in Africa’s role in the global economy might be over the coming decades. Given its demographic explosion while population growth in the rest of the world stagnates, we outline two trajectories for how this might play out:

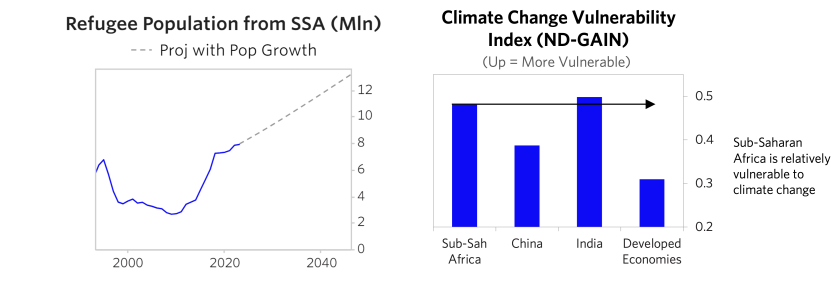

- Still very undeveloped, but larger: over the past 40 years, sub-Saharan Africa has made less progress in rising out of poverty than other major population centers like India and China. Productivity growth has averaged only around 1%, leading to only small gains in GDP per capita. If this trend continues, sub-Saharan Africa will still have one of the highest GDP growth rates in the world, given that its working-age population will grow 2-3% (while others are barely growing or shrinking). Its share of the world economy will increase, but not by much, and it will remain not very relevant to the global economy. In this scenario, there could be geopolitical consequences as a growing share of the global population is “left behind,” exacerbating migration pressures (especially as climate shocks intensify), increasing global poverty and income inequality, and fueling further political instability.

- Emerging out of poverty: there is also a path where sub-Saharan Africa begins to experience the sort of upswing in development, productivity, and standard of living that economies like India have experienced in recent decades—not a China-level productivity miracle, but a classic phase of catch-up growth that we have seen in other major emerging market population centers. On this path, sub-Saharan Africa would become more akin to the larger economies in emerging Asia today in its importance to the global economy and relevance to global investors.

Without big changes, our long-term growth estimates are unfortunately for a scenario closer to the first case than the second. In either case, it will take a long time for this region to become relevant to the global economy. As shown below, if productivity growth can rise to 4%, sub-Saharan Africa will begin to emerge out of poverty and play a more meaningful role in the global economy.

The Coming Demographic Shifts Will Make Sub-Saharan Africa a Large Share of the World’s Working Age Population

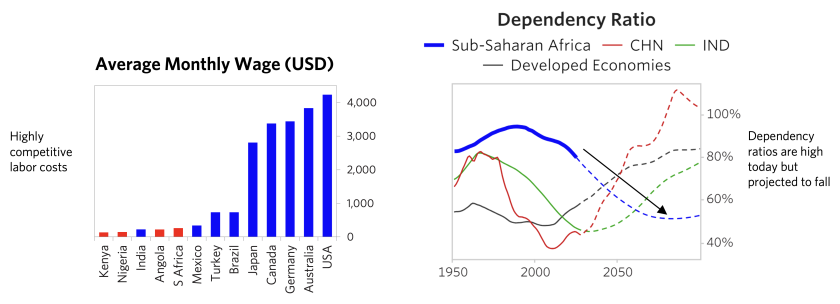

Sub-Saharan Africa’s working-age population is projected to grow by about 70% over the next 20 years (an annualized rate of about 2.7%). This is much faster than any other region in the world. The comparable rate for India is about 0.6%, while working-age population is projected to shrink in the developed economies and China (by about -0.4% and -0.8% per year respectively). The rapid growth in sub-Saharan Africa’s population reflects the combination of a fertility rate that is much higher than any other region’s with rising life expectancies, especially as a result of declining infant mortality rates. Moreover, the share of the region’s population that is of working age is rising; its median age is just 18, well below the global median of 31. This both boosts labor-force growth and has implications for productivity, as we discuss in more detail below.

Productivity Growth Has Been Extremely Slow, with Little Recent Progress in Emerging Out of Poverty

Even with anemic productivity growth, the demographic baseline means that sub-Saharan Africa will likely grow as a share of global GDP (and correspondingly, production, demand, trade, markets, etc.)—but it will remain quite small. Unfortunately, that is the growth trajectory the region has been on. Over the past 40 years, GDP per capita in sub-Saharan Africa has been relatively flat, and it has not experienced the same upward swing in development, productivity, and standard of living as other major emerging population centers (notably China starting around 1980, and then in more recent decades India).

If the region remains as poor as it is today, this significant increase in sub-Saharan Africa’s population is likely to magnify a range of geopolitical challenges. Today, incomes in the region remain low, food insecurity is relatively widespread, and as much as 80% of employment is in the informal sector. These dynamics have been significant drivers of migration, largely within Africa and to Europe (where it, along with migration from other regions, has had meaningful knock-on effects on European politics). These pressures are also important drivers of political instability within the region and are likely to become even more significant as climate shocks intensify (with sub-Saharan Africa being one of the most vulnerable regions in the world to those shocks).

Given the Fundamentals Today, Our Base-Case Estimate Is That Long-Term Productivity Growth Will Be Mediocre

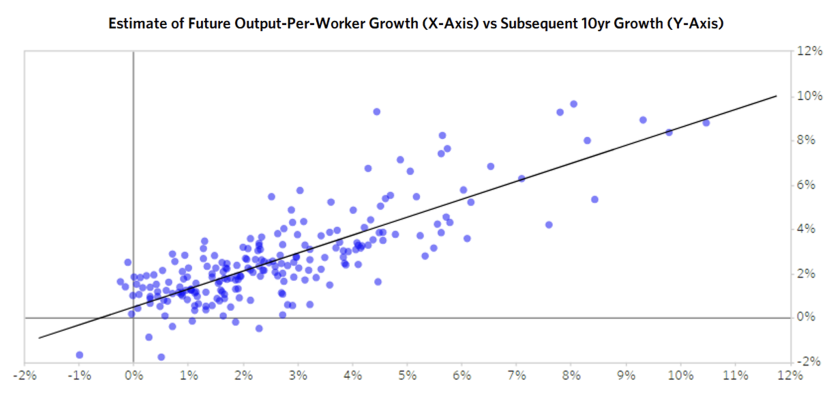

We have studied the long-term drivers of growth and built a process for estimating the 10-year growth of economies from a variety of logical indicators. At the top level, growth is driven by growth in working-age population and growth in output per worker. Output per worker is in turn driven by productivity growth (which is in turn driven by competitiveness, amount of investment, quality of institutions, etc.) and indebtedness (which impacts how much swings in credit can be a headwind or a tailwind). As shown in the scatter below, this process yields a reasonably reliable estimate (tested across 40 countries, 70 years of history, and a wide range of environments), though there are divergences, and every case has elements the framework did not capture adequately.

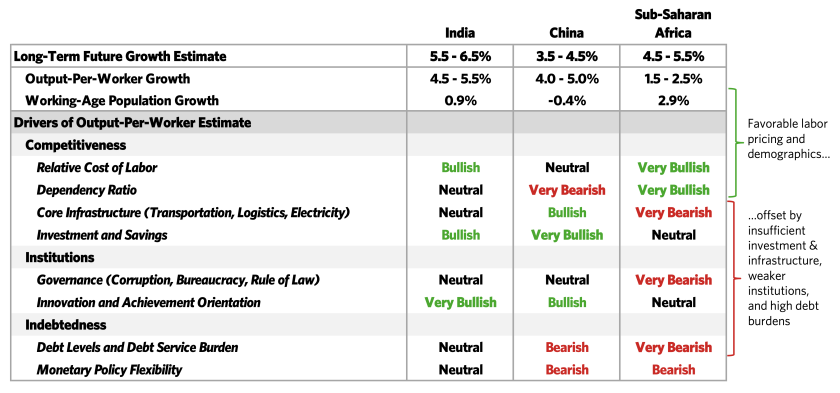

Applying this framework to the economies of sub-Saharan Africa, our base case for long-term productivity growth in the region is positive but low, around 2%. This would be an improvement from the past decade of relative stagnation but will still keep the region in poverty with limited impact on the rest of the world in the coming decades. Combined with working-age population growth of a little under 3%, this yields a future growth estimate of 4.5-5.5%, compared to 3.5-4.5% for China and 5.5-6.5% for India.

The biggest tailwinds are very favorable labor pricing and demographic shifts. As a relatively low-income region, labor is priced very cheaply relative to most of the rest of the world (though other barriers limit the region’s ability to capitalize on that competitive position, which we discuss next). On demographics, beyond a quickly growing labor force, falling dependency ratios (ratio of non-working-age population to working-age population) create the potential for a “demographic dividend” to play out. As dependency ratios fall, people in the region are likely to be able to save a higher share of their incomes, which can fuel productive investments and growth. This is effectively the opposite of what we see in the developed world and China, where aging populations (i.e., rising dependency ratios) are contributing to a buildup of “IOUs.”

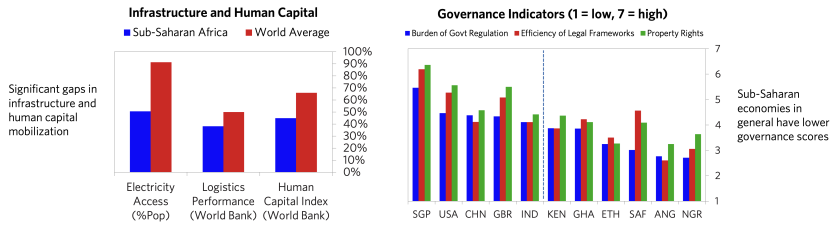

On the other hand, the region faces several major headwinds. First, it lacks core infrastructure (transportation, logistics, and electricity) and invests less in human capital, which undermines labor competitiveness. In addition, the region generally has weaker institutions than middle- and higher-income countries (with greater risk of corruption, more bureaucracy, and weaker rule of law), which undermines the attractiveness of doing business and investing in the region.

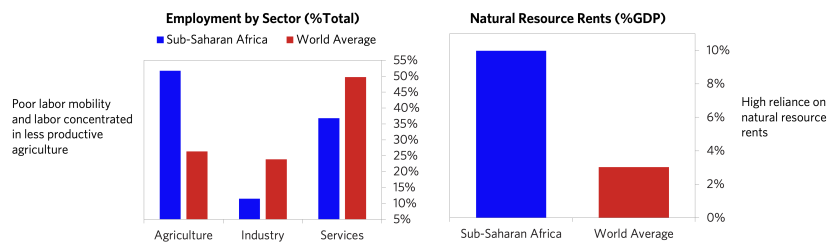

Second, the economies are generally less flexible and less diversified. Employment is concentrated in agriculture (which tends to be less productive) relative to industry and services, and labor mobility is poor. And rents on natural resources make up a large share of output, so swings in the commodity cycle drive big swings in growth and government revenues (for instance, this was a big tailwind from 2000 - 14, and then a big headwind in the five years after).

Third, external debt service has risen to an unsustainable share of government revenues (in many places more than is spent on education or healthcare). Rising rates in the developed world have flowed through to higher hard currency borrowing rates (reflecting the need for tighter monetary policy in places like the US but creating an undesirable headwind for sub-Saharan African economies, many of which are barely above pre-COVID output levels). On top of that, sub-Saharan African countries face much higher credit spreads than typical emerging market borrowers. Since 2020, Ghana, Zambia, and Ethiopia have all defaulted on their foreign debts.

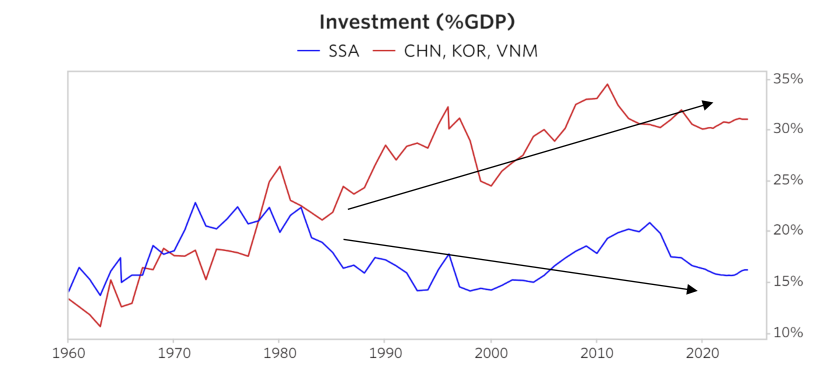

Lastly, the overall level of investment is low relative to what is needed to support a boom in productivity. High investment levels boost productivity by increasing the ratio of capital relative to labor, laying foundational infrastructure such as roads and electrical grids, and investing in human capital through education and healthcare. While other factors were also at play, very high levels of investment and savings (versus consumption spending) were a big driver of the productivity booms in many East Asian economies over the past 40 years. By contrast, the investment rates in sub-Saharan Africa were and remain much lower, only around half of the amount in places like China, Korea, and Vietnam.

This research paper is prepared by and is the property of Bridgewater Associates, LP and is circulated for informational and educational purposes only. There is no consideration given to the specific investment needs, objectives, or tolerances of any of the recipients. Additionally, Bridgewater's actual investment positions may, and often will, vary from its conclusions discussed herein based on any number of factors, such as client investment restrictions, portfolio rebalancing and transactions costs, among others. Recipients should consult their own advisors, including tax advisors, before making any investment decision. This material is for informational and educational purposes only and is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy the securities or other instruments mentioned. Any such offering will be made pursuant to a definitive offering memorandum. This material does not constitute a personal recommendation or take into account the particular investment objectives, financial situations, or needs of individual investors which are necessary considerations before making any investment decision. Investors should consider whether any advice or recommendation in this research is suitable for their particular circumstances and, where appropriate, seek professional advice, including legal, tax, accounting, investment, or other advice. No discussion with respect to specific companies should be considered a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular investment. The companies discussed should not be taken to represent holdings in any Bridgewater strategy. It should not be assumed that any of the companies discussed were or will be profitable, or that recommendations made in the future will be profitable.

The information provided herein is not intended to provide a sufficient basis on which to make an investment decision and investment decisions should not be based on simulated, hypothetical, or illustrative information that have inherent limitations. Unlike an actual performance record simulated or hypothetical results do not represent actual trading or the actual costs of management and may have under or overcompensated for the impact of certain market risk factors. Bridgewater makes no representation that any account will or is likely to achieve returns similar to those shown. The price and value of the investments referred to in this research and the income therefrom may fluctuate. Every investment involves risk and in volatile or uncertain market conditions, significant variations in the value or return on that investment may occur. Investments in hedge funds are complex, speculative and carry a high degree of risk, including the risk of a complete loss of an investor’s entire investment. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a complete loss of original capital may occur. Certain transactions, including those involving leverage, futures, options, and other derivatives, give rise to substantial risk and are not suitable for all investors. Fluctuations in exchange rates could have material adverse effects on the value or price of, or income derived from, certain investments.

Bridgewater research utilizes data and information from public, private, and internal sources, including data from actual Bridgewater trades. Sources include BCA, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Bond Radar, Candeal, CBRE, Inc., CEIC Data Company Ltd., China Bull Research, Clarus Financial Technology, CLS Processing Solutions, Conference Board of Canada, Consensus Economics Inc., DataYes Inc, Dealogic, DTCC Data Repository, Ecoanalitica, Empirical Research Partners, Entis (Axioma Qontigo Simcorp), EPFR Global, Eurasia Group, Evercore ISI, FactSet Research Systems, Fastmarkets Global Limited, the Financial Times Limited, FINRA, GaveKal Research Ltd., Global Financial Data, GlobalSource Partners, Harvard Business Review, Haver Analytics, Inc., Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), the Investment Funds Institute of Canada, ICE Derived Data (UK), Investment Company Institute, International Institute of Finance, JP Morgan, JSTA Advisors, M Science LLC, MarketAxess, Medley Global Advisors (Energy Aspects Corp), Metals Focus Ltd, Moody’s ESG Solutions, MSCI, Inc., National Bureau of Economic Research, Neudata, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Pensions & Investments Research Center, Refinitiv, Rhodium Group, RP Data, Rubinson Research, Rystad Energy, S&P Global Market Intelligence, Scientific Infra/EDHEC, Sentix GmbH, Shanghai Metals Market, Shanghai Wind Information, Smart Insider Ltd., Sustainalytics, Swaps Monitor, Tradeweb, United Nations, US Department of Commerce, Verisk Maplecroft, Visible Alpha, Wells Bay, Wind Financial Information LLC, Wood Mackenzie Limited, World Bureau of Metal Statistics, World Economic Forum, and YieldBook. While we consider information from external sources to be reliable, we do not assume responsibility for its accuracy.

This information is not directed at or intended for distribution to or use by any person or entity located in any jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability, or use would be contrary to applicable law or regulation, or which would subject Bridgewater to any registration or licensing requirements within such jurisdiction. No part of this material may be (i) copied, photocopied, or duplicated in any form by any means or (ii) redistributed without the prior written consent of Bridgewater® Associates, LP.

The views expressed herein are solely those of Bridgewater as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice. Bridgewater may have a significant financial interest in one or more of the positions and/or securities or derivatives discussed. Those responsible for preparing this report receive compensation based upon various factors, including, among other things, the quality of their work and firm revenues.