The unprecedented pace of government action on climate looks unlikely to continue, as voters and policy makers grapple with the economic trade-offs.

Since the 2016 Paris Agreement, developed world governments have enacted substantial policies to incentivize the green transition. Across the United States, United Kingdom, and Europe, governments have pursued a variety of policies to subsidize investment in green technologies and penalize the use of fossil fuels.

These large-scale industrial policies have increasingly begun to affect economic outcomes, in both positive and negative ways. The climate transition will require a massive overhaul of the world’s physical infrastructure, which necessitates disruptions to supply chains, jobs, investment flows, and consumer behavior. Many of these changes are now starting to bite, creating headwinds for the green transition. For example, carbon pricing (e.g., pollution taxes) has exacerbated concerns around the rising cost of living in the EU, supply squeezes (e.g., fossil fuel restrictions) are seen as a threat to the oil and gas industry in certain US states, and green fiscal spending (e.g., subsidies for renewable energy) has sparked painful fiscal constraints, such as the specter of higher taxes in the UK.

While households still care about climate issues, they are now taking a backseat to more pressing economic concerns as the potential trade-offs become more apparent. With upcoming elections in the United States and a shift in the balance of power after recent elections in Europe, the likelihood is growing that we see a continued slowdown in—or in some cases, even a partial rollback of—key climate policies.

The exact nature of this pushback is different across geographies—because they have passed different policies and are facing different economic conditions—but it represents a significant change to the trend over the last decade and has knock-on effects for companies and their strategic plans. For example, changes to government targets to phase out internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles in the UK will impact how profitable new electric vehicle (EV) facilities will turn out to be. For investors and companies that want to support cutting emissions and a transition to net zero, the balance between financial and non-financial goals is also likely to become increasingly challenging.

In the rest of this report, we describe these trade-offs and their consequences for policy in more detail.

Current Policies Are Insufficient for Meeting Climate Goals but Are Still Running into Constraints

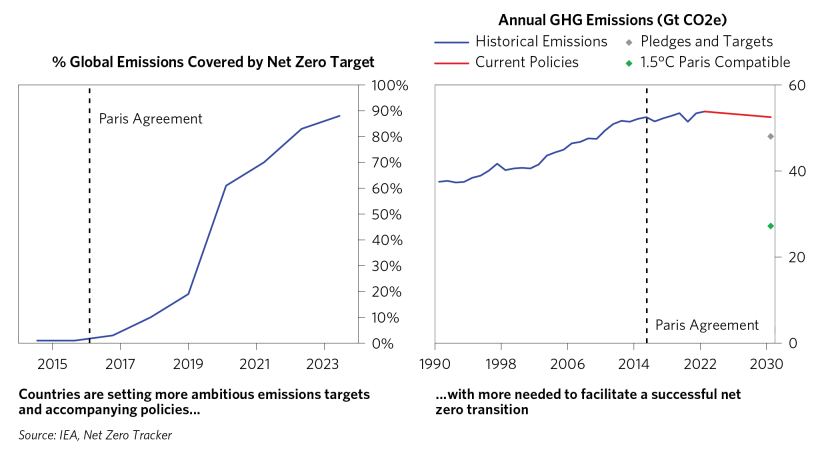

Since the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2016, countries around the world have started to set ambitious targets to reduce their emissions. More than 80% of global emissions, including major emitters such as China, the US, India, and the EU, are now covered by a national net zero target, but the reality is that current policies are insufficient to meet these goals. As shown below, while policies to date have contributed to a stabilization of global emissions, which have been rising over the last century, they will only lead to a modest fall in global emissions over the next decade. More action is needed if governments are to reach their emission reduction targets, let alone limit global temperature rises to 1.5°C.

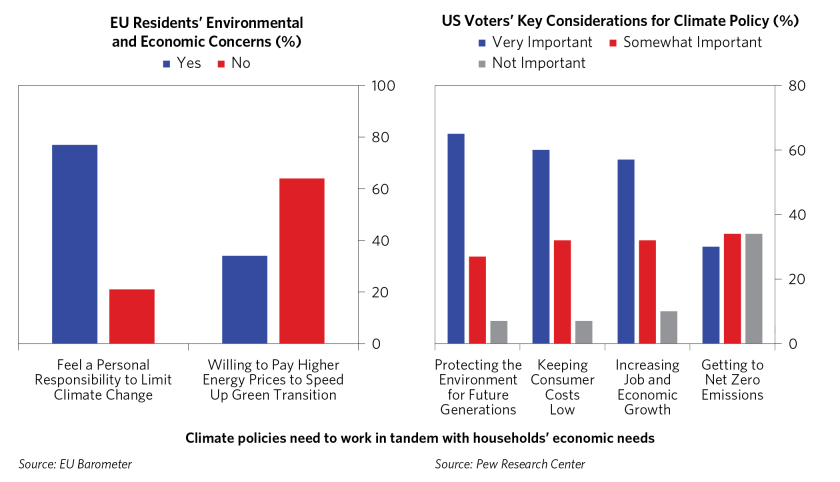

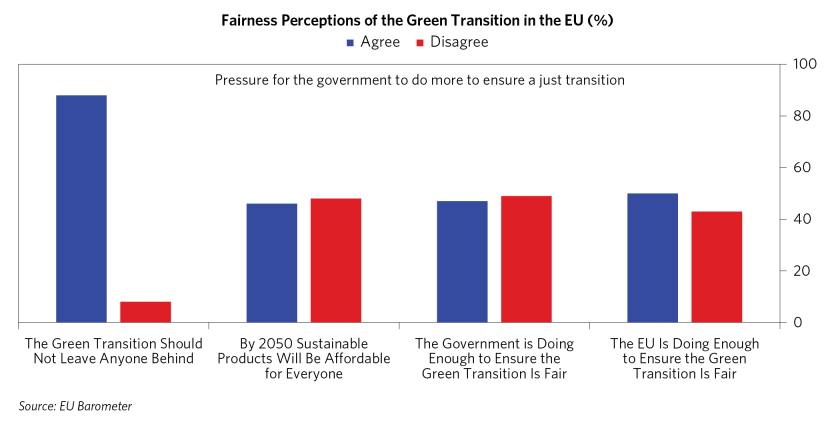

The period during which today’s policies were passed coincided with favorable economic conditions, such as secularly low inflation (especially in Europe). Since then, inflation has risen to decades-long highs, and climate policies themselves are also starting to bite as their costs become increasingly spread across the economy—e.g., more sectors being added to the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), households needing to pay directly for pollution taxes, auto workers seeing their jobs under threat as internal combustion engine production slows down. These trade-offs are being reflected in voter preferences: while they continue to recognize the importance of environmental issues, the vast majority of voters only express support for climate action if it does not come at the expense of their economic needs. In the EU, despite most residents stating they feel a “personal responsibility” to limit climate change, far fewer are willing to do so if it involves paying higher energy prices. Similarly, support for climate policies in the United States is far more likely if these policies balance environmental goals with keeping consumer costs low or increasing employment and economic growth.

Because different geographies have relied on different climate policy levers, the challenges they are running into—and the trade-offs that they are facing—also vary meaningfully. We provide more detail on these policies in the appendix, but at a headline level:

- Europe—which has historically focused on a “stick”-based approach to disincentivize emissions—has seen the greatest challenges balancing climate and the economy. For example, voters are pushing back on the withdrawal of agricultural diesel subsidies (which raises expenditures for farmers), regulations mandating the installation of heat pumps (which have higher upfront costs than gas boilers), and accelerated phaseout timelines for ICE vehicles (particularly in countries with large auto manufacturing employment).

- The United States—where subsidies have been the main policy lever—has seen more mild opposition to climate policies (though it’s hard to see much more action going forward). Even a second Trump presidency is unlikely to fully reverse what’s been done already, although his campaign speeches have targeted the perceived threat to fossil fuel and auto industry jobs.

- The United Kingdom—which recently elected a new Labour government—has focused on green policies that require lower direct fiscal outlays (e.g., reducing barriers to private sector infrastructure investment), due to concerns that subsidies would need to be funded by higher taxes at a time when deficits are already stretched. There is also uncertainty around ICE phaseouts after the timeline was pushed back by the previous Conservative government, which could affect investment in electric vehicles.

In the following pages, we walk through the different types of climate policies (i.e., carbon pricing, supply squeeze, and green fiscal spending), and their economic trade-offs (e.g., inflation, jobs, competitiveness, government debt). While we focus on developed world economies in this report as they make up the largest share of investor portfolios, other high-emitting countries (e.g., China, India) are unlikely to make up for lost ground. Although they are adding meaningful green energy capacity, their overall energy needs are growing even more rapidly and hence continue to support demand for fossil-based energy.

Carbon Pricing Is Stretching Household Transportation and Energy Expenditures

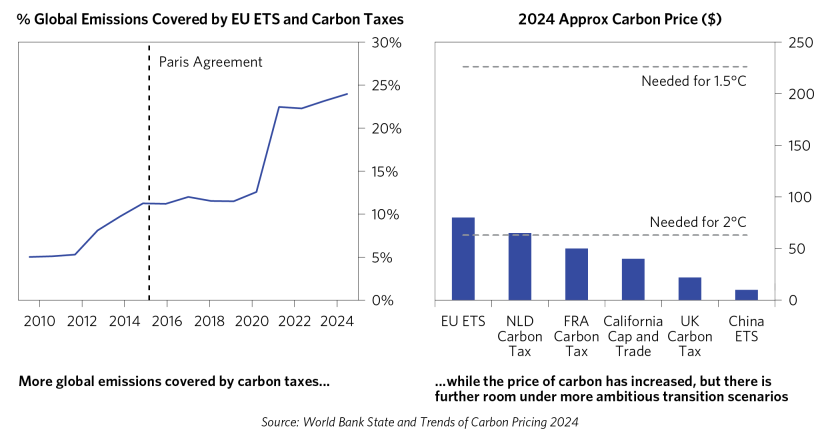

Almost a quarter of global emissions now fall under carbon pricing schemes, which is a significant increase from a decade prior. In Europe, the EU ETS covers 40% of the region’s emissions—with plans to incorporate new sectors, such as buildings and road transportation, and to expand coverage in existing sectors, such as shipping—while many EU member states have also implemented taxes on ICE vehicles or fossil-based electricity. In the United States, there is no national carbon pricing mechanism, but regional initiatives, such as California’s cap-and-trade system or the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, have been in place for many years and are complemented by newer programs, such as Washington’s cap-and-invest program. Meanwhile, the price of carbon under these schemes has risen over the last decade but is still short of the levels needed to create large-scale behavioral changes and cap global temperature rises to a reasonable level.

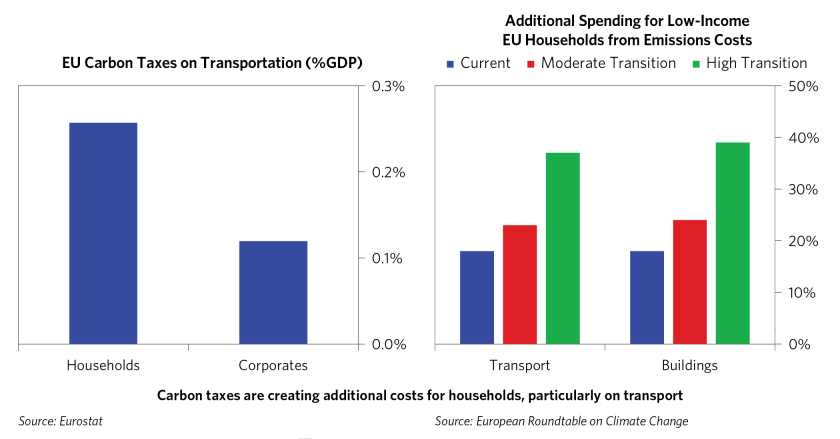

Because carbon pricing works by imposing an additional cost on emissions-intensive processes, it is by nature inflationary. While the majority of these costs are borne by businesses (as they account for a larger share of global emissions), measures that affect households—such as pollution taxes for ICE vehicles—have started to face pushback from voters. For example, Portugal scrapped its single circulation tax increase after a petition signed by 400,000 people concerned about higher costs to commuters, while in the United Kingdom, criticism of the expansion of London's Ultra Low Emission Zone was cited as one of the reasons for Labour’s by-election losses in Uxbridge and South Ruislip. As shown below, EU households today shoulder most of the burden of carbon taxes on transportation, with this amount set to increase further with the planned expansion of the EU ETS (which will include emissions from road transport and residential buildings).

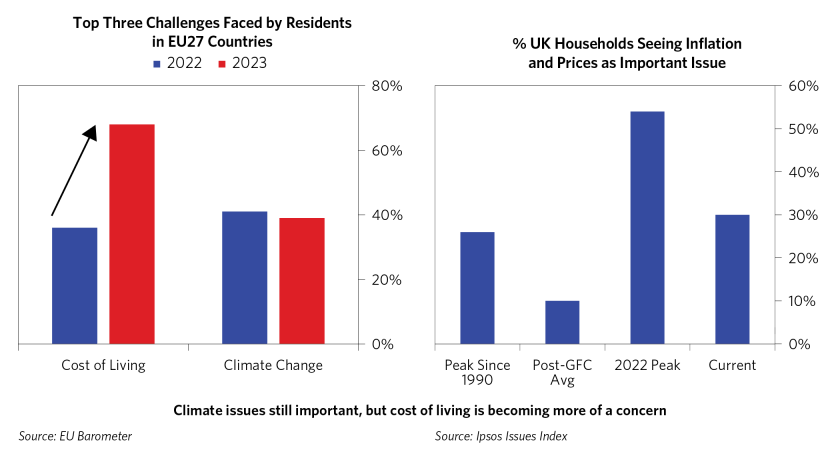

These pressures come at a time when inflation has been secularly high—and thus rising to the top of the list of voters’ concerns—which has called into focus climate policies that are seen as exacerbating the cost-of-living crisis. According to a Gallup poll, more than a third of voters cited economic issues as their biggest concern in 2024, compared to ~10% during the last election cycle. Similarly in the EU, more than two-thirds of respondents cited the cost of living as one of their top three challenges in 2023—more than double that in 2022. And in the UK, voter concerns over inflation have risen to their highest level in decades (despite a pullback from the recent peak).

Policies to address other impacts of carbon pricing—such as loss of competitiveness—can also exacerbate inflation. The EU, for example, is introducing a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) to prevent “carbon leakage,” whereby domestic goods and services struggle to compete against cheaper imports that did not have to pay for their emissions, or industries move abroad to geographies with no carbon pricing. However, the way the CBAM addresses competitiveness is by increasing the price of imports—both for intermediate use in manufacturing or final goods for consumption—which creates further inflationary pressures at a time when household balance sheets are already stretched.

Fossil Fuel Phaseouts Are Disrupting Jobs and Local Economies

In addition to pricing in negative externalities from carbon, transitioning to a net zero economy will also entail cutting back on high-emitting fossil-fuel-based products and replacing them with green alternatives, particularly in sectors where the technology is already feasible, such as electricity or transportation. As shown below, governments around the world have set phaseout targets for high-emitting products, such as coal or ICE vehicles, many of which are backed up by national legislation and policies.

As with carbon pricing, these policies can lead to increased costs for households in the short run, as many green technologies require higher upfront costs (despite providing savings over their lifespan). In Germany, most households cited costs (e.g., inability to afford the investment or thinking that the investment is not worthwhile) as their main reason for opposing the installation of heat pumps, which has become a high-profile election issue. Yet, in the same survey, households that had already switched to heat pumps also reported feeling much lower price pressures compared to households that stuck with fossil-fuel-based heating systems.

Beyond inflation, supply squeeze measures are also creating significant disruptions to local economies, particularly those reliant on high-emitting industries. As shown below, while the green transition is on net likely to create more jobs than it destroys, the negative impacts are likely to be concentrated in fossil fuels or auto manufacturing, which is also where opposition to green policies has been the most vocal. In the United States, auto workers and unions in Michigan and Wisconsin have expressed concerns over the pace of the EV transition, which were amplified by Donald Trump’s campaign speeches and contributed to a watering down of the EPA’s final regulations on vehicle tailpipe emissions. Similarly in the EU, countries with large auto industries, such as Germany (5% of GDP) and Italy (8.5% of GDP), have pushed back against an accelerated ICE phaseout—securing an exception for ICE vehicles running on carbon-neutral “e-fuels”—while the planned closure of coal mines in countries like Bulgaria has sparked protests from affected workers.

Governments can play an important role in mitigating some of these concerns, and they are being pressured to modify their policies to address the adverse economic effects of the green transition. The EU, for example, has allocated resources from the Just Transition Fund to regions with high employment in heavy industry, coal and lignite mining, and oil production, and it is rolling out the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism to support industries affected by the loss of competitiveness created by carbon pricing. In the United States, states with large fossil fuel industries, such as Colorado or New Mexico, have launched just transition initiatives to channel investments toward workers affected by the climate transition, although less has been done at the federal level.

Green Fiscal Spending Is Running into Budgetary Constraints

Finally, in addition to the “stick”-based approaches of carbon pricing and supply squeeze measures, governments have also increased their spending on incentives, such as subsidies or tax credits, for climate-aligned activities, beginning with the Inflation Reduction Act in the United States and Europe’s response in the form of the Net Zero Industry Act. While there has been less direct pushback from voters on green fiscal policies—largely because subsidies reduce the direct costs faced by households (even though the broader spending is potentially inflationary)—governments are running into constraints on how to finance climate spending while still maintaining fiscal discipline. In the United States, for example, the Congressional Budget Office has already revised its projections for expenditures under the Inflation Reduction Act upward by $428 billion, due to a higher-than-expected take-up rate on subsidies for electric vehicles, battery manufacturing, and renewable energy.

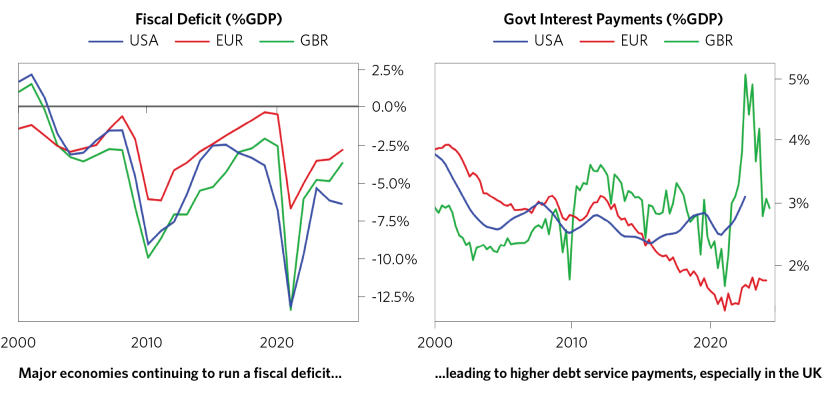

As shown below, many countries with large climate packages already run consistent fiscal deficits, while debt service costs have also ticked upward over the last few years. This makes financing new climate spending increasingly challenging, especially as governments need to weigh other competing priorities. The UK spent more money on debt service than education in 2022, and the incoming Labour government has backtracked on its proposed GBP 28 billion annual green investment plan amid concerns that the scheme would need to be financed by higher taxes. Elsewhere in Europe, Germany’s supreme court has blocked the reallocation of COVID funds to subsidize green technologies such as heat pumps, and the incoming European Parliament plans to focus on implementing existing portions of the European Green Deal—rather than formulating new policies—as member states will need to approve an expansion of EU fiscal capacity before more spending can be undertaken.

Government spending on green technologies, however, typically receives more support when it is seen as complementary to energy security and hence stable and affordable energy prices for households. In the United Kingdom, which has high offshore-wind potential and has recently faced record-high gas prices, investment in renewable energy is seen as a critical part of the Labour government’s strategy to lower energy bills and increase energy security, overseen by the aptly named Department of Energy Security and Net Zero. By contrast, in the United States—where some states have large oil and gas industries, and others have abundant wind and solar resources—there is a partisan split on whether increasing renewable energy production would make it easier or harder to achieve domestic energy security.

A Delayed Transition Would Have Implications on Companies’ Green Capex and Transition Inputs

The shift in policy has knock-on effects for companies and their strategic plans. As shown below, almost all public companies have developed plans to reduce their emissions, and a meaningful share has followed up with tangible investments, with government policy being a major input into their decisions.

Many of these investments could be put at risk in the case of a protracted pushback against climate policies. For example, auto companies in the UK have already expressed reluctance to scale up their green investments amid an uncertain policy environment, where the planned 2030 ICE phaseout target was delayed to 2035 by the previous Conservative government. Because of the longer time horizon associated with green investments, companies often require greater assurances on future cash flows for these decisions to make financial sense, which is harder in a world where there is a risk of policies getting reversed or delayed in the next election cycle.

Volkswagen: “We urgently need a clear and reliable regulatory framework which creates market certainty and consumer confidence, including binding targets for infrastructure rollout and incentives to ensure the direction of travel.”

Kia: “Today's announcement...alters complex supply chain negotiations and product planning, whilst potentially contributing to consumer and industry confusion.”

Ford: “Our business needs three things from the UK government: ambition, commitment, and consistency. A relaxation of 2030 would undermine all three. We need the policy focus trained on bolstering the EV market in the short term and supporting consumers while headwinds are strong.”

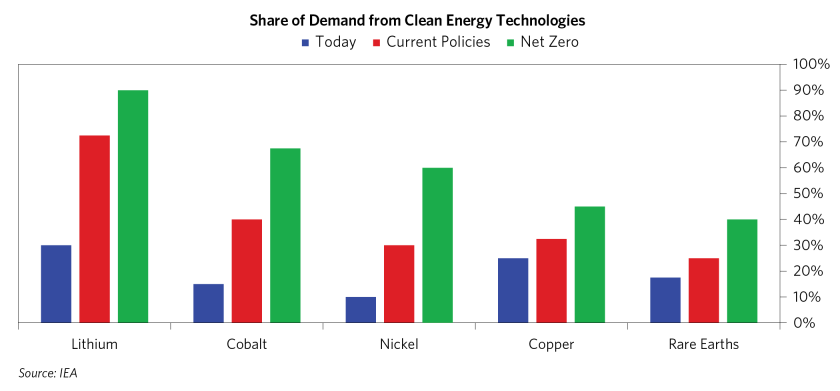

A shift in the world’s emissions reduction trajectory would also affect demand and supply for many inputs to the transition, such as commodities that are used in electric vehicles or renewable energy. As shown below, green technologies are a major source of demand for critical minerals such as lithium or nickel, and the dynamics of these markets—such as capital investment, exploration of new reserves, and processing and refining capacity—would vary significantly under different net zero scenarios.

Appendix: Examples of Pushback on Current Climate Policies & Positions of Major Parties

This research paper is prepared by and is the property of Bridgewater Associates, LP and is circulated for informational and educational purposes only. There is no consideration given to the specific investment needs, objectives, or tolerances of any of the recipients. Additionally, Bridgewater's actual investment positions may, and often will, vary from its conclusions discussed herein based on any number of factors, such as client investment restrictions, portfolio rebalancing and transactions costs, among others. Recipients should consult their own advisors, including tax advisors, before making any investment decision. This material is for informational and educational purposes only and is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy the securities or other instruments mentioned. Any such offering will be made pursuant to a definitive offering memorandum. This material does not constitute a personal recommendation or take into account the particular investment objectives, financial situations, or needs of individual investors which are necessary considerations before making any investment decision. Investors should consider whether any advice or recommendation in this research is suitable for their particular circumstances and, where appropriate, seek professional advice, including legal, tax, accounting, investment, or other advice. No discussion with respect to specific companies should be considered a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular investment. The companies discussed should not be taken to represent holdings in any Bridgewater strategy. It should not be assumed that any of the companies discussed were or will be profitable, or that recommendations made in the future will be profitable.

The information provided herein is not intended to provide a sufficient basis on which to make an investment decision and investment decisions should not be based on simulated, hypothetical, or illustrative information that have inherent limitations. Unlike an actual performance record simulated or hypothetical results do not represent actual trading or the actual costs of management and may have under or overcompensated for the impact of certain market risk factors. Bridgewater makes no representation that any account will or is likely to achieve returns similar to those shown. The price and value of the investments referred to in this research and the income therefrom may fluctuate. Every investment involves risk and in volatile or uncertain market conditions, significant variations in the value or return on that investment may occur. Investments in hedge funds are complex, speculative and carry a high degree of risk, including the risk of a complete loss of an investor’s entire investment. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a complete loss of original capital may occur. Certain transactions, including those involving leverage, futures, options, and other derivatives, give rise to substantial risk and are not suitable for all investors. Fluctuations in exchange rates could have material adverse effects on the value or price of, or income derived from, certain investments.

Bridgewater research utilizes data and information from public, private, and internal sources, including data from actual Bridgewater trades. Sources include BCA, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Bond Radar, Candeal, CBRE, Inc., CEIC Data Company Ltd., China Bull Research, Clarus Financial Technology, CLS Processing Solutions, Conference Board of Canada, Consensus Economics Inc., DataYes Inc, Dealogic, DTCC Data Repository, Ecoanalitica, Empirical Research Partners, Entis (Axioma Qontigo Simcorp), EPFR Global, Eurasia Group, Evercore ISI, FactSet Research Systems, Fastmarkets Global Limited, the Financial Times Limited, FINRA, GaveKal Research Ltd., Global Financial Data, GlobalSource Partners, Harvard Business Review, Haver Analytics, Inc., Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), the Investment Funds Institute of Canada, ICE Derived Data (UK), Investment Company Institute, International Institute of Finance, JP Morgan, JSTA Advisors, M Science LLC, MarketAxess, Medley Global Advisors (Energy Aspects Corp), Metals Focus Ltd, Moody’s ESG Solutions, MSCI, Inc., National Bureau of Economic Research, Neudata, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Pensions & Investments Research Center, Refinitiv, Rhodium Group, RP Data, Rubinson Research, Rystad Energy, S&P Global Market Intelligence, Scientific Infra/EDHEC, Sentix GmbH, Shanghai Metals Market, Shanghai Wind Information, Smart Insider Ltd., Sustainalytics, Swaps Monitor, Tradeweb, United Nations, US Department of Commerce, Verisk Maplecroft, Visible Alpha, Wells Bay, Wind Financial Information LLC, Wood Mackenzie Limited, World Bureau of Metal Statistics, World Economic Forum, and YieldBook. While we consider information from external sources to be reliable, we do not assume responsibility for its accuracy.

This information is not directed at or intended for distribution to or use by any person or entity located in any jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability, or use would be contrary to applicable law or regulation, or which would subject Bridgewater to any registration or licensing requirements within such jurisdiction. No part of this material may be (i) copied, photocopied, or duplicated in any form by any means or (ii) redistributed without the prior written consent of Bridgewater® Associates, LP.

The views expressed herein are solely those of Bridgewater as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice. Bridgewater may have a significant financial interest in one or more of the positions and/or securities or derivatives discussed. Those responsible for preparing this report receive compensation based upon various factors, including, among other things, the quality of their work and firm revenues.